Hoa Lo Prison / Hanoi Hilton: History, Tours, and Visitor Guide | Vietnam Purple Travel Guide

(map, reviews, website)

This is Premium Content! To access it, please download our

Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel GuideOpening Hours: 8am – 5pm daily

Admission: 50,000 VND per adult at the time of writing

Multi Lingual Audio Guide Rental: 50,000 VND

Warning: Hoa Lo Prison is an intense experience. Viewer discretion, especially with small kids, is advised.

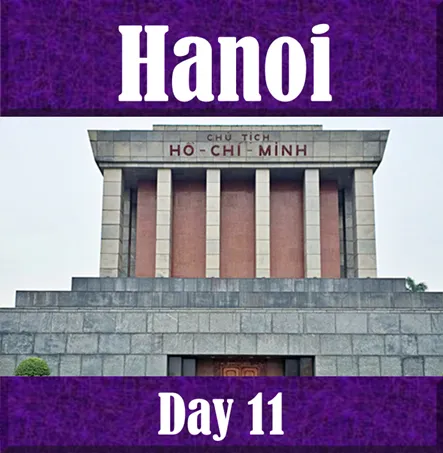

Hoa Lo Prison = Hanoi Hilton

Hoa Lo Prison is often referred to as the ‘Hanoi Hilton’. It stands as a poignant reminder of Vietnam’s turbulent past. This historical site offers visitors a chance to explore the harsh realities faced by prisoners during both the French colonial era and the Vietnam War.

Visiting Hoa Lo Prison offers a profound insight into Vietnam's colonial and wartime history. The museum's exhibits provide a tangible connection to the past, allowing visitors to understand the struggles and resilience of those who endured imprisonment. It is an opportunity to reflect on the human capacity for endurance and the importance of historical memory in shaping a nation's identity.

Historical Background of Hoa Lo Prison Museum

French Colonial Era (1896–1954)

Constructed between 1896 and 1901 by the French colonial administration, Hoa Lo Prison — known as Maison Centrale — was designed to incarcerate Vietnamese political prisoners advocating for independence. The prison's name, Hỏa Lò, translates to ‘fiery furnace’, a term that reflects both the intense heat of the region and the brutal conditions within the prison walls. Overcrowding was a persistent issue; in 1916, the facility held 730 inmates, a number that surged to 895 by 1922 and 1,430 by 1933.

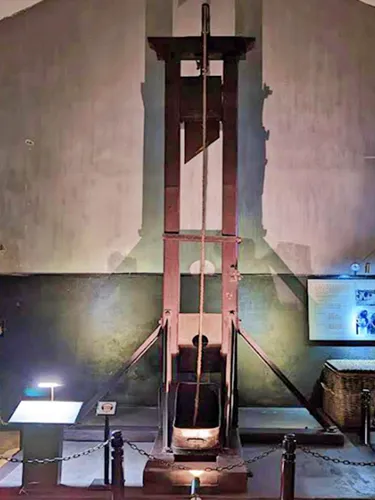

Prisoners endured severe conditions, including forced labor, inadequate food, and physical abuse. The infamous French guillotine, displayed in the museum, was used for executions during this period, underscoring the extreme measures employed by colonial authorities to suppress dissent.

Vietnam War Era (1964–1973)

Following the French withdrawal in 1954, Hoa Lo Prison was repurposed by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to detain American prisoners of war (POWs). The facility became known to American POWs as the ‘Hanoi Hilton’, a term that, despite its ironic connotation, reflected the prison's notoriety for its harsh conditions.

Notable American POWs held here included Senator John McCain, who was shot down in 1967 and spent over five years in captivity. The museum provides insights into the experiences of these prisoners, highlighting their resilience and the complex dynamics between captors and captives.

John McCain's Experience at Hoa Lo Prison

John McCain, a U.S. Navy aviator, became one of the most famous prisoners of war (POWs) held at Hoa Lo Prison during the Vietnam War. On October 26, 1967, McCain was shot down while flying a bombing mission over Hanoi. His aircraft, a Skyhawk A-4, was struck by a missile, and McCain was forced to eject. He suffered significant injuries during the crash, breaking both arms and a leg, and was unable to swim to safety as he fell into the Truc Bach Lake, where he was captured by North Vietnamese soldiers. Despite his severe injuries, McCain was taken to Hoa Lo Prison, where he began his five and a half years of captivity.

Upon arrival at Hoa Lo, McCain was placed in solitary confinement, an experience that would last for much of his imprisonment. The conditions were deplorable, with inadequate food, unsanitary conditions, and a complete lack of medical care for his broken limbs. The North Vietnamese prison guards subjected him to brutal torture, including physical beatings and psychological abuse. McCain later recounted the intense isolation and the dehumanizing treatment he faced. His arms and leg were never properly treated, leading to lifelong disabilities, and he was frequently denied pain relief or medical assistance. Despite this, McCain’s resolve remained strong, and he continued to refuse to cooperate with his captors.

The North Vietnamese, recognizing McCain's family connections — his father was Admiral John S. McCain Jr., a respected commander of U.S. naval forces in the Pacific — offered him early release in 1968. The release was part of a broader strategy to manipulate American POWs into appearing as though the U.S. was forced to surrender or negotiate. However, McCain, adhering to the military code of conduct, refused the offer. He stated that he would only accept release after all POWs captured before him were freed, making a significant moral stand that would define his character.

During his time at Hoa Lo, McCain was moved to a series of different cells, many of them small, dark, and filthy. The solitary confinement was an attempt to break his spirit, but McCain, along with other American prisoners, found ways to communicate through tapping on the walls and developed a sense of camaraderie and unity despite the isolation. He later described how this mutual support was essential to his survival.

In 1973, after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, McCain and other American POWs were released in Operation Homecoming. McCain’s return was widely celebrated, though he came back to the U.S. with lasting physical and emotional scars from his years of torture. His time at Hoa Lo was a critical part of his life’s story, shaping his later political career, particularly his work on veterans' affairs, as he became an advocate for the treatment and recognition of former POWs.

At Hoa Lo Prison, a section of the museum is dedicated to McCain’s experience. It includes personal items from his time as a prisoner, such as a flight suit, photographs of him in captivity, and a small replica of the cell where he was held. His story is integral to understanding the larger narrative of the American POW experience at Hoa Lo, symbolizing the resilience, sacrifice, and unyielding determination of the men who endured the horrors of this notorious prison.

Post-War Period and Museum Establishment

After the reunification of Vietnam in 1975, Hoa Lo Prison continued to function as a detention center until 1993. Recognizing its historical significance, the Vietnamese government preserved a portion of the original structure, transforming it into a museum that opened to the public in 1996. Today, the museum serves as an educational site, offering visitors a comprehensive look into the country's colonial and wartime history.

What to See at Hoa Lo Prison Museum

Colonial Prison Cells

The museum preserves several original prison cells, providing a stark portrayal of the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions endured by inmates. Visitors can observe the cramped spaces and minimal furnishings that characterized daily life for prisoners during the French colonial period.

Execution Chamber with Guillotine

A chilling highlight is the preserved execution chamber, featuring a French guillotine used during the colonial era. This grim artifact underscores the extreme measures taken by authorities to suppress resistance and maintain control over the population.

Exhibits on American POWs

Dedicated sections of the museum focus on the experiences of American POWs held during the Vietnam War. Artifacts, photographs, and personal accounts shed light on the hardships faced by these individuals and their eventual release following Operation Homecoming.

Reconstructed Cells and Artifacts

The museum has reconstructed several cells using original materials, including bricks and concrete, to provide an authentic representation of the prison environment. Artifacts such as shackles, uniforms, and personal items offer tangible connections to the past.

The Tropical Almond Tree

In the prison's courtyard stands a nearly century-old tropical almond tree, the last remaining from the French colonial era. This tree served as a source of sustenance for prisoners, with its fruits and leaves providing nourishment during their confinement.

Today, the tree symbolizes resilience and endurance.

Here at Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides, we promote self-guided walking tours.

But we realize that not everybody likes to walk by themselves in a foreign city. So, just in case that you rather go with ab guide: NO PROBLEM! Please see the GuruWalk and Viator tours below.

free GuruWalk tours

paid Viator tours

Where do you want to go now?

Author: Rudy at Backpack and Snorkel

Bio: Owner of Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides. We create in-depth guides to help you plan unforgettable vacations around the world.

Other popular Purple Travel Guides you may be interested in:

Like this Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel Guide? Pin these for later: