Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum & Visitor Guide: Honor Vietnam's Father | Vietnam Purple Travel Guide

(map, reviews)

This is Premium Content! To access it, please download our

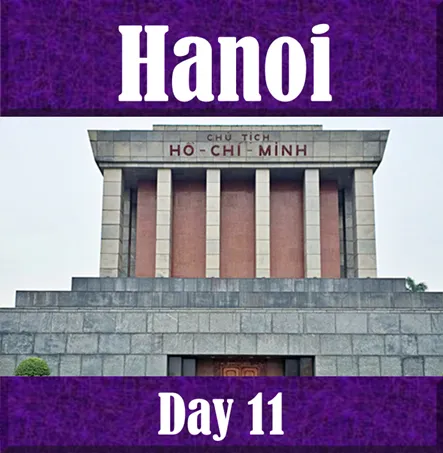

Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel GuideThe Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum (Lăng Chủ tịch Hồ Chí Minh) stands as one of the most solemn and significant landmarks in Vietnam. Located at the heart of Ba Đình Square in Hanoi, this granite monument houses the embalmed body of President Hồ Chí Minh, the revolutionary leader who guided Vietnam to independence and remains a deeply respected figure in the nation's modern history. A visit to the mausoleum is not only a chance to witness a rare, preserved body but also a moment of reverence and national pride, offering insight into Vietnam’s struggle for sovereignty and the values its people hold dear.

Here are some photos that we took:

Who Was Ho Chi Minh? – The Life and Legacy of Vietnam’s Revolutionary Leader

Hồ Chí Minh (born Nguyễn Sinh Cung, 1890–1969) was the founding father of modern Vietnam, a revolutionary leader, statesman, and powerful symbol of Vietnamese nationalism. He was the primary force behind the country’s struggle for independence from French colonial rule, the defeat of foreign imperialist powers, and the formation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). Known affectionately as ‘Bác Hồ’ (Uncle Ho) by the Vietnamese people, he remains a deeply revered figure whose name, image, and ideals continue to influence Vietnam to this day.

Early Life and Education

Hồ Chí Minh was born on May 19, 1890, in the village of Kim Liên in Nghệ An Province, central Vietnam. His birth name was Nguyễn Sinh Cung, though he would later adopt numerous aliases throughout his life. His father, a Confucian scholar and teacher, instilled in him a strong sense of Vietnamese identity and patriotism.

At a young age, Hồ Chí Minh left Vietnam to pursue education and explore the world. In 1911, he worked as a kitchen assistant on a French steamship and spent several years traveling to France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other parts of the world. These travels exposed him to the harsh realities of colonialism, racism, and class inequality—experiences that would deeply shape his political ideology.

Political Awakening and Revolutionary Ideology

In France, Hồ became involved with socialist and anti-colonial circles. He joined the French Communist Party in 1920 and began advocating for the independence of Vietnam and other colonized nations. He published articles under the pen name Nguyễn Ái Quốc (‘Nguyen the Patriot’) and gained international attention for his writings on colonial injustice.

Hồ Chí Minh later traveled to Moscow to study Marxist-Leninist theory and received revolutionary training from the Communist International (Comintern). He believed that communism offered a path not only to end colonial oppression but also to build a just and egalitarian society in Vietnam. In 1930, he helped establish the Indochinese Communist Party, which would become the ideological nucleus of Vietnam’s independence movement.

Fight for Independence and the Birth of North Vietnam

During World War II, while Vietnam was under Japanese occupation, Hồ returned to lead a communist-led resistance group called the Việt Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam). Following Japan’s defeat in 1945, Hồ Chí Minh seized the opportunity to declare Vietnam’s independence from France. On September 2, 1945, he stood in Ba Đình Square in Hanoi and proclaimed the birth of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, reading a declaration of independence that echoed the words of both the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man.

However, France refused to relinquish its former colony, and the First Indochina War broke out between French forces and the Việt Minh. After nearly a decade of conflict, the French were defeated in 1954 at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ. The Geneva Accords that followed divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel: Hồ Chí Minh became President of North Vietnam, while the U.S.-backed Republic of Vietnam was established in the south.

The Vietnam War and Hồ Chi Minh’s Final Years

From the mid-1950s onward, Hồ Chí Minh focused on building a socialist state in the North while supporting revolutionary forces in the South, known as the Viet Cong, in their fight against the South Vietnamese government and its American allies. This conflict escalated into the full-blown Vietnam War (known in Vietnam as the Resistance War Against America), a protracted and devastating struggle that drew the attention of the entire world.

Hồ Chí Minh remained a central symbolic and strategic figure in this period, though by the late 1960s, his health began to decline. He died on September 2, 1969, exactly 24 years after declaring Vietnam’s independence. His passing was a deeply emotional moment for the nation, which was still in the midst of war.

Legacy of Ho Chi Minh

Today, Hồ Chí Minh is remembered not only as a revolutionary leader but as a symbol of national unity, humility, and resilience. His portrait hangs in classrooms, government buildings, and family homes across the country. The former city of Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City in his honor in 1976, following the reunification of Vietnam under communist rule.

What Did Ho Chi Minh Believe?

Hồ Chí Minh’s political philosophy was a blend of Marxist-Leninist theory, Vietnamese nationalism, and Confucian humanism. He championed:

National independence and anti-colonialism

Social justice and the redistribution of wealth

Educational reform, especially literacy and access to learning

Modesty and service, famously living in a simple stilt house rather than the Presidential Palace

While his leadership contributed to the establishment of a single-party socialist state, sometimes criticized for political repression, many Vietnamese continue to regard him with great affection for his sacrifices, personal integrity, and unwavering dedication to national liberation.

Ho Chi Minh's Mausoleum - A Monument of Reverence: History and Symbolism

Construction of the mausoleum began on September 2, 1973, exactly four years after Hồ Chí Minh’s death, and was completed in 1975. Although Uncle Ho, as he is affectionately known by the Vietnamese, had requested a simple cremation, the Communist Party decided to preserve his body and build a grand mausoleum, inspired in part by Lenin’s tomb in Moscow. The design combines Soviet monumental architecture with Vietnamese architectural elements, such as the sloping roof resembling traditional pagodas, symbolizing a harmonious blend of ideology and local culture.

The mausoleum was erected on the site of Ba Đình Square, where Hồ Chí Minh proclaimed Vietnam’s independence from French colonial rule on September 2, 1945, making the location historically and symbolically powerful. The project was supported by the Soviet Union, whose influence is evident in the austere lines and monumental scale of the structure.

The building is made of grey granite on the outside and polished red, black, and grey stone on the inside. Above the main portico, the words ‘CHỦ TỊCH HỒ CHÍ MINH’ (President Ho Chi Minh) are inscribed in bold capital letters. The structure rises to a height of 71 ft (21.6 m) and is surrounded by manicured gardens and stately flagpoles, projecting both authority and reverence.

What to See Inside and Around the Mausoleum Complex

The Embalmed Body of Hồ Chí Minh

The central experience of visiting the mausoleum is viewing the embalmed body of Hồ Chí Minh, preserved in a climate-controlled glass case, dimly lit and guarded by uniformed soldiers. Visitors move through the room silently and without stopping. The body lies in repose, dressed in a simple khaki uniform, representing his famously modest lifestyle. The preservation of his body is a delicate annual task, every year it is sent to Russia for maintenance by experts.

Ba Đình Square

Before or after visiting the mausoleum, take time to walk across the vast Ba Đình Square in front of the structure. This is the most politically important square in the country, where military parades and national ceremonies are held. The square is divided into 240 grassy plots arranged symmetrically and flanked by national flags and flower beds.

Ho Chi Minh’s Stilt House

Located behind the mausoleum is the Ho Chi Minh Residence, where the President lived from 1958 until his death in 1969. This traditional wooden stilt house reflects Ho’s personal philosophy of simplicity and frugality. Inside, you can see his bedroom, study, and personal belongings, preserved to look exactly as they did in the 1960s. The garden surrounding the house features a carp pond and shady paths.

Presidential Palace

Although Hồ Chí Minh declined to live in the opulent Presidential Palace, the yellow neoclassical building is visible from the grounds and was used by him for official meetings and diplomatic receptions.

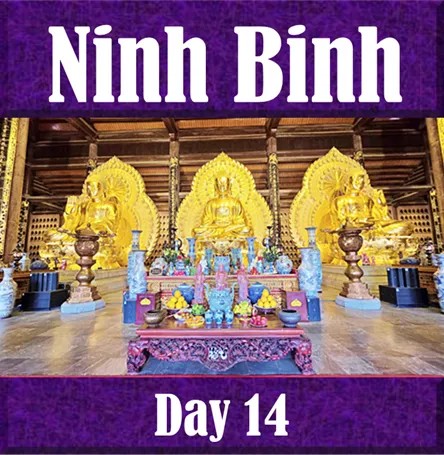

One Pillar Pagoda

Adjacent to the mausoleum complex is the famous One Pillar Pagoda (Chùa Một Cột), an iconic Buddhist structure built originally in 1049. Shaped like a lotus blossom rising from a single stone pillar, it represents purity and enlightenment and makes for a serene and photogenic side visit.

Admission Fee, Visiting Hours, and Regulations

Admission Fee

Free of charge to visit the mausoleum and Ba Đình Square.

Entry to the stilt house and museum: 40,000 VND (~US$1.60)

Discounts apply for students and children.

Opening Hours

Mausoleum Hours (for viewing the body):

7:30 AM to 10:30 AM, Tuesday to Thursday and Saturday to Sunday

Closed on Monday and Friday

Closed annually during October and November for maintenance (check locally for exact dates)

Stilt House and Museum Hours:

7:30 AM to 4:00 PM (with a lunch break from 11:00 AM–1:30 PM)

Security & Visitor Etiquette:

Ba Đình Square

No chewing gum allowed - yes, they enforce this

Need to pass through metal detector to enter the site.

Mausoleum

Strict dress code: No shorts, sleeveless shirts, hats, or chewing gum allowed inside.

No talking, photography, or stopping inside the mausoleum chamber.

Bags, cameras, and large items must be checked at security.

Need to pass through metal detectors and to be escorted in groups along a designated path.

Here at Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides, we promote self-guided walking tours.

But we realize that not everybody likes to walk by themselves in a foreign city. So, just in case that you rather go with ab guide: NO PROBLEM! Please see the GuruWalk and Viator tours below.

free GuruWalk tours

paid Viator tours

Where do you want to go now?

Author: Rudy at Backpack and Snorkel

Bio: Owner of Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides. We create in-depth guides to help you plan unforgettable vacations around the world.

Other popular Purple Travel Guides you may be interested in:

Like this Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel Guide? Pin these for later: