Humayun's Tomb: The UNESCO Blueprint for the Taj Mahal | India Purple Travel Guide

(map, reviews, website)

This is Premium Content! To access it, please download our

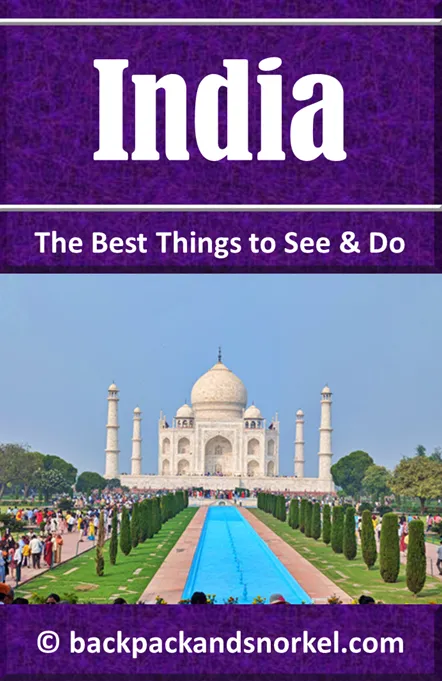

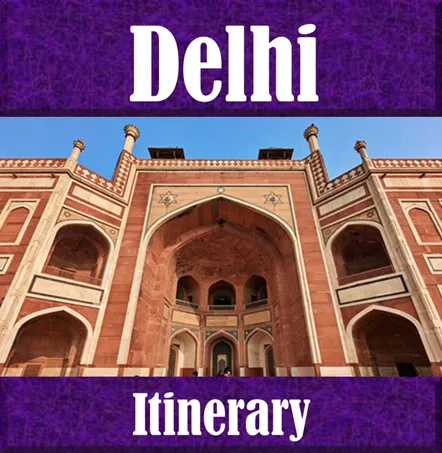

Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel GuideHumayun's Tomb is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a breathtaking piece of architecture that bridges the gap between earlier central Asian mausoleums and the ultimate expression of Mughal funerary architecture: the Taj Mahal in Agra, built nearly a century later.

Here at Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides, we promote self-guided walking tours.

But we realize that not everybody likes to walk by themselves in a foreign city. So, just in case that you rather go with ab guide: NO PROBLEM! Please see the GuruWalk and Viator tours below.

free GuruWalk tours

paid Viator tours

Why You Must Visit

Precursor to the Taj Mahal: Humayun's Tomb introduced several design elements, most notably the Charbagh garden and the use of the double-dome, which were perfected in the Taj Mahal.

Architectural Serenity: Unlike the busy Red Fort, the complex offers much more space and quietude. The vast, geometrically arranged gardens provide a peaceful, meditative atmosphere.

Historical Significance: It houses the body of the second Mughal Emperor, Humayun, and contains over 150 graves of Mughal royalty, earning it the nickname, ’Dormitory of the Mughals’.

Admission Fee and Opening Hours

Admission Fee: Foreign Tourists: ₹600 (at the time of writing).

Photography and Videography: photography is allowed and free of charge, and Video filming permit is ₹25 per person.

Opening Hours: Open daily from sunrise to sunset (typically 6:00 AM to 6:00 PM).

Best Time to Visit: Early morning at opening time to avoid the midday heat and the main crowds. The light is also best for photography.

Time Needed: Budget 90 to 120 minutes to comfortably explore the main tomb and surrounding gardens and structures.

History and Importance

The tomb was commissioned in 1569 by Hamida Banu Begum, Humayun’s Persian wife, nine years after the Emperor’s death. Its construction signaled the return of Mughal power to India under Humayun's son, Akbar the Great, after a ‘Period of Exile’ from 1540–1555. In this 15-year period between the reigns of the second and third emperors, the Mughal dynasty lost control of India.

The Loss of Power: Emperor Humayun inherited the throne from his father, Babur, but was defeated and driven out of India in 1540 by the Afghan ruler Sher Shah Suri.

The Exile: Humayun was forced to flee west, spending years wandering through Persia (modern-day Iran) and Afghanistan. During this time, his son, Akbar, who would become the greatest of the Mughal emperors, was born in exile.

The Return: In 1555, with Persian military aid, Humayun successfully defeated the successors of Sher Shah Suri and regained the throne of Delhi. However, he died tragically just six months later after falling down the stairs of his library.

More details about the tomb:

Persian Influence: Its design marks the first major infusion of Persian architecture into the Indian subcontinent. The chief architect, Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, was Persian, and he brought with him the concept of the octagonal central chamber and the expansive, symmetrical garden plan.

The Final Resting Place: The tomb served as the primary burial site for Mughal emperors and family members for nearly 300 years (first burial: 1570, last burial: 1856), reinforcing its importance as a dynastic mausoleum.

British Connection: The last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was captured here by the British in 1857, marking the official end of the Mughal Empire in India.

Architecture and Design

The tomb is the first structure in India built in the Charbagh style, a quadrilateral garden layout based on the four gardens of Paradise mentioned in the Quran.

The Tomb Structure: The main mausoleum sits on a massive, two-tiered stone plinth. It is constructed primarily of red sandstone, beautifully contrasted with white marble used for the dome, ornamental inlay, and borders.

The Double Dome: The dome itself is revolutionary for its time, featuring a double layer—a tall outer shell providing the iconic silhouette and a lower inner shell creating an intimate ceiling for the burial chamber. This technique was vital for future Mughal structures.

Symmetry and Water: The Charbagh is divided into four main sections by walkways and two central water channels that represent the four rivers of Paradise. The intricate geometric symmetry is a defining feature of the entire complex.

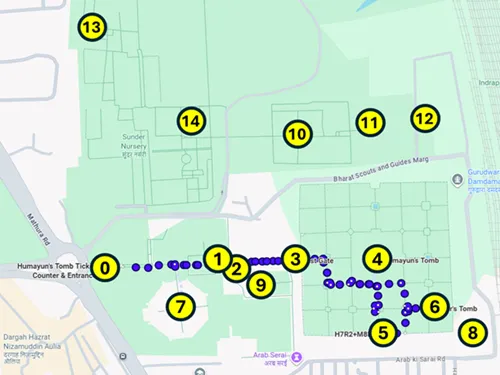

Self-Guided Walking Tour of the Humayun's Tomb Complex

The complex is vast and extends beyond the main mausoleum. The structures surrounding Humayun's Tomb will help you understand the site's rich historical and architectural context.

As the site is vast, and we don’t have unlimited time, we have designed a Self-Guided Walking Tour of structures 1-7 inside the Humayun's Tomb Complex. Feel free to visit structures 8-14, if you have time.

Start at the ticket office labeled 0.

0 = Entrance

1 = Bu Halima Gate

2 = Arab Serai Gate

3 = West Gate

4 = Humayun’s Tomb

5 = South Gate

6 = Barbers Tomb

7 = Isa Khan Tomb

8 = Nila Gumbad

9 = Afsarwala Tomb

10 = Mirza Muzaffar Hussain Tomb

11 = Chota Batashewala Tomb

12 = Unknow Mughal’s Tomb

13 = Lakkarwala Burj

14 = Sunderwala Mahal

Bu Halima's Gate

The Bu Halima's Gate marks the initial entry point into the sprawling Humayun's Tomb complex. While it may appear modest compared to the subsequent structures, this gateway, and the small tomb behind it are essential for understanding the transitional and ceremonial function of the complex, serving as a prelude to the grandeur of the main mausoleum.

Feature |

Detailed History and Significance |

|---|---|

History & The Bu Halima Mystery |

The identity of Bu Halima is uncertain. She was likely a highly respected wet nurse (Anaga or Daya) or a noblewoman attached to the Mughal court, possibly during the time of Babur (Humayun's father). Wet nurses and their families often gained immense political and social power within the royal structure, warranting a prominent tomb site. |

Architecture |

The gate is a two-story structure built of sturdy red sandstone and rubble masonry, featuring a single, deep central arch. It is stylistically simpler than the grand gates that would later define the Charbagh surrounding Humayun's Tomb, representing an earlier, transitional phase in Mughal architecture. |

Bu Halima's Tomb |

Immediately inside the gateway lies Bu Halima’s Tomb. This small, simple, square structure rests on a raised platform (chabutra). Its understated design is typical of earlier Mughal tomb architecture—a crucial contrast to the colossal scale and complex ornamentation of Humayun’s Tomb nearby. |

Garden Design |

The small area surrounding the tomb, known as Bu Halima’s Garden, is designed as a less formal version of the Charbagh layout. It features basic symmetrical water channels and walkways, establishing the expectation of the much larger, more perfect paradise garden that awaits the visitor deeper within the complex. |

Importance to the Visit |

This spot is essential because it functions as the ceremonial forecourt. It serves as a psychological boundary, separating the chaos of the outside world from the solemn, spiritual order of the complex. While you may only stop briefly, it sets the stage for the meticulous planning and symmetrical perfection of the main site. |

Arab Serai Gate

The Arab Serai Gate marks the entrance to a crucial, yet often overlooked, part of the Humayun's Tomb complex: the residential and logistical quarter built specifically to house the workforce for the monumental construction project. This massive gate emphasizes security and scale, giving insight into the organization required for such an ambitious undertaking.

Feature |

Detailed History and Significance |

|---|---|

History & Purpose |

The Arab Serai (Caravan Stop or Inn) and its gate were built by Humayun’s chief consort, Hamida Banu Begum, in the 1560s. The structure was designed to provide secure lodging for the hundreds of Persian artisans, craftsmen, calligraphers, and workers who were brought from Persia (modern-day Iran) to build Humayun's Tomb. |

Architecture |

The gate is a massive, imposing structure built using robust rubble masonry and fortified with prominent turrets and solid bastion walls. Its sheer scale and defensive appearance underscore its role as the single, secured entry point to the residential quarter. It needed to protect both the highly skilled workforce and the precious building materials stored inside. |

The Serai Quarter |

Inside the gate lay the Serai itself—a vast, walled courtyard designed to serve as a self-contained, temporary town. It included residential cells, stables, storage areas, and probably small workshops. This entire quarter was necessary because the Mughal capital was still in flux during the early years of Akbar’s reign, and skilled foreign labor required maximum security. |

Importance to Construction |

The gate and the protective walls of the Serai are essential evidence of the complex logistics and security measures required to execute the tomb’s design. The use of Persian artisans ensured that the tomb incorporated the latest Persian architectural ideas, making it the first significant example of the Indo-Persian synthesis that would define later Mughal building (like the Taj Mahal). |

The Experience |

Admiring the sheer thickness and height of the gate walls allows you to appreciate the practical challenges faced by the builders. It represents the ‘behind-the-scenes’ military and logistical planning necessary to execute a masterpiece of this scale. |

West Gate

The West Gate is the primary entrance for modern visitors to Humayun's Tomb, and historically, it was the grand ceremonial entrance. Its architecture is specifically designed to create a moment of awe, offering the first impressive, sweeping view of the vast Charbagh Garden and the magnificent tomb at its center.

Feature |

Detailed History and Significance |

|---|---|

Primary Function |

The gate served as the grand ceremonial entrance into the main Charbagh complex. Its placement ensured that the visitor’s first glance captured the full, symmetrical glory of the tomb and its surrounding paradise garden, exactly as the Empress Hamida Banu Begum intended. |

Architecture |

It is an imposing, rectangular structure built primarily of rich red sandstone, beautifully framed by white marble inlay. It features a large central arch flanked by smaller arches on either side. |

The Chhatri Detail |

The gate is crowned by a striking chhatri—a raised, dome-shaped pavilion (chhatri literally means ‘umbrella’ or ‘canopy’ in Hindi). These features are classic Mughal design elements, symbolizing honor, nobility, and royalty. The chhatri adds elegance and visual height to the structure. |

Ceremonial Approach |

The transition through the West Gate is deliberate. Upon passing through the deep, shaded archway, the visitor emerges into the bright light of the garden, facing the tomb’s massive red sandstone and marble base. This controlled revelation is a masterstroke of early Mughal architectural planning. |

Importance to the Visit |

As the main entry point, the West Gate not only guides traffic but establishes the monumental scale and the Indo-Persian style that defines the complex. It signals that the visitor is leaving the secular world and entering a sacred, meticulously ordered space. |

Humayun's Tomb (The First Garden-Tomb)

Please also see the description earlier in this chapter.

The Maqbara-i Humayun (Tomb of Humayun) is the central and most magnificent structure of the complex. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the first substantial example of the great Mughal architectural style, defining the aesthetic principles that would later culminate in the Taj Mahal.

Feature |

Detailed History, Architecture, and Significance |

|---|---|

Patron & Date |

Commissioned by Humayun's chief consort, Empress Hamida Banu Begum, in 1565 CE, nine years after his death. The construction was overseen by her and completed in 1572 CE, marking a powerful, early example of female patronage in Mughal architecture. |

Chief Architect |

Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, a highly regarded Persian architect. His presence ensured the tomb incorporated the latest and most advanced Persian architectural ideas. |

Architectural Style |

Indo-Persian Synthesis. This tomb is the first major structure to successfully merge the massive scale and chhatri (pavilion) elements of Indian tradition with the delicate geometry and precise symmetry of classical Persian architecture. |

Layout (Hasht Bihisht) |

The interior layout follows the crucial Islamic concept of Hasht Bihisht (Eight Paradise). The central tomb chamber (containing the sarcophagus) is an octagon surrounded by eight smaller octagonal chambers, creating a perfectly symmetrical, multi-room structure symbolizing paradise. |

The Double Dome |

This is the tomb's most significant innovation in India. It features a Persian-style double dome—an inner shell for the low ceiling of the interior chamber and a high outer shell to give the structure its monumental height and imposing presence. This revolutionary technique was later perfected in the Taj Mahal. |

Materials & Finish |

The building is constructed primarily of vibrant red sandstone, beautifully offset by extensive use of white marble inlay and trim, particularly on the dome and around the deep, arched entryways (iwans). This defining color contrast became the hallmark of Mughal imperial architecture. |

The 'Dormitory of the Mughals' |

The inner vaults and corner chambers of the structure contain the graves of over 150 members of the Mughal royal family across several generations, earning it the affectionate nickname, ‘The Dormitory of the Mughals.’ |

The Interior Experience |

The massive central chamber contains a large, plain sarcophagus of Humayun, positioned exactly beneath the high outer dome. The light filtering through the intricately carved marble jali (screens) creates a solemn, spiritual, and perfectly geometric atmosphere. |

South Gate

The South Gate and the nearby Nai ka Gumbad (Tomb of the Barber) are essential structures that define the southern axis of the Humayun's Tomb complex. They underscore the meticulous symmetry of the Mughal design, while the tomb offers a fascinating glimpse into the social hierarchy of the royal court.

Feature |

Detailed History and Significance |

|---|---|

Architecture (South Gate) |

The South Gate is structurally similar in style and material to the main West Gate, built of robust red sandstone with a large central arch. It maintains all the essential features of Mughal gateway architecture, including rhythmic symmetry and framed entryways. Its key architectural role is to complete the four-sided perimeter of the garden complex. |

Historical Function |

This gate originally served as the secondary, or rear, ceremonial entry point. It was critical not for daily traffic, but for maintaining the strict architectural symmetry of the massive Charbagh plan, ensuring the geometric perfection demanded by the Persian design. |

Traveler's Note (Access) |

This gate is closed to the public today and is not used for entry or exit. We went through the gate and a guard called us back, prohibiting access to the area behind the gate, even though visible signage confirming the closure was absent. Please respect the instructions of the site staff. |

Nai ka Gumbad (The Tomb of the Barber) |

Situated inside the main Charbagh, this small, distinctive tomb is locally and popularly identified as the final resting place of the royal barber (Nai in Hindi). The occupant is officially unknown, but the legend speaks volumes about the level of intimacy, trust, and influence a valued servant could attain within the Mughal imperial household. |

Architectural Contrast (Nai ka Gumbad) |

The Tomb of the Barber is stylistically distinct, often attributed to the Lodi period or an early Mughal construction. It is a simple, square structure topped by an unusual domed roof resting on a raised platform, offering a fascinating contrast to the immense scale and Indo-Persian style of Humayun’s Tomb itself. |

Overall Importance |

This area is vital for appreciating the complete cosmic symmetry of the complex—the idea that the perfect Charbagh garden must have four equal gates facing the cardinal directions. It shows the meticulous planning that went into the entire imperial funerary landscape. |

Barber's Tomb (Nai ka Gumbad)

The Nai ka Gumbad (Tomb of the Barber) is one of the most intriguing satellite tombs within the Humayun's Tomb complex. Its prominence within the sacred garden layout speaks volumes about the influence and trust earned by non-royal personnel in the Mughal court, even if the occupant’s true identity remains unknown.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

Popular Name |

Nai ka Gumbad (Tomb of the Barber). Local legend maintains that this is the resting place of Humayun's highly esteemed personal barber (Nai), signifying the intimacy and high status such a close court attendant could achieve. |

Location |

The tomb holds a prime location—it is situated directly within the meticulously planned Charbagh Garden, near the central pathway and the southeast corner of the main mausoleum’s perimeter. This placement suggests the buried person held a position of considerable importance to the Mughal family. |

Architecture |

The structure is a simple, elegant square tomb built primarily of red sandstone. It stands on a slightly elevated platform (chabutra). Its most striking feature is its single dome, which is notably simpler in design than the advanced double-dome of Humayun’s Mausoleum. |

Architectural Contrast |

The Nai ka Gumbad provides a crucial stark contrast to the vast scale and architectural complexity of Humayun’s Tomb. Its single-chambered, unadorned elegance represents a purer, perhaps earlier, form of Lodi or early Mughal tomb design, highlighting the evolution of imperial architecture seen across the complex. |

Historical Importance |

Regardless of who lies beneath the dome, its location confirms that the site was considered sacred and reserved for the most important figures in the imperial circle. This inclusion within the royal funerary landscape is a testament to the fact that power and status in the Mughal court were not solely based on bloodline. |

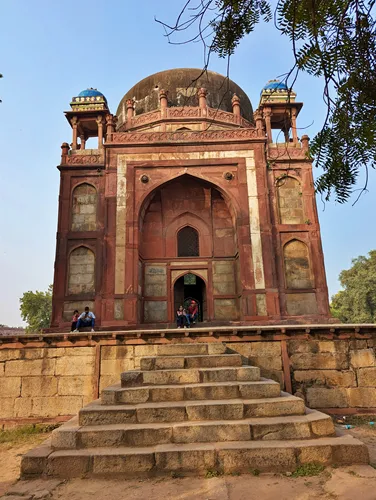

Isa Khan's Tomb and Mosque

The complex containing the tomb of Isa Khan Niyazi is a beautiful, essential stop within the Humayun's Tomb grounds, one that you should not miss before you exit the site. Interestingly, this tomb and its adjacent mosque predate Humayun's Tomb by two decades, providing invaluable architectural context to the entire era.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

History & Context |

The tomb belongs to Isa Khan Niyazi, an influential Afghan nobleman who served as a key courtier to Sher Shah Suri. Sher Shah was the Afghan ruler who temporarily defeated and exiled Humayun from India (1540-1555 CE). The tomb's date of completion, 1547 CE, clearly marks it as a structure of the Sur Dynasty that occupied the throne between the first and second Mughal Empires. |

Architecture: The Octagonal Plan |

Isa Khan's Tomb is a splendid, well-preserved example of Lodi-era or Afghan-style tomb architecture. Its distinctive design is based on the octagonal plan, a tomb chamber surrounded by a wide, open verandah with three arches on each of the eight sides. This highly recognizable shape contrasts sharply with the massive, square Mughal mausoleum nearby. |

The Jama Masjid (The Adjacent Mosque) |

Adjacent to the tomb, and located within the same walled compound, stands a small but elegant mosque. This mosque is structurally integral to the complex, built primarily of red sandstone and known for its three arched openings (bays). The entire enclosure was designed as a single religious and funerary unit, a characteristic typical of the pre-Mughal period. |

Architectural Features |

The tomb is crowned with characteristic chattris (domed kiosks) on the roof, and the exterior walls feature beautiful and intricate glazed blue tile work, which is a key decorative feature of the period. This use of ceramic tiling provides a perfect architectural comparison to the later, more refined stone-inlay style of the Mughals. |

Importance to the Visit |

Isa Khan's Tomb reminds visitors that the Mughals were not the sole masters of Delhi during this period. It allows you to track the evolution of tomb architecture from the Afghan style (octagonal, heavy use of tiles) to the mature Mughal style (square, double-dome, red sandstone, and marble inlay) perfected in Humayun's Tomb. |

The Experience |

The tomb complex is surrounded by its own small, peaceful courtyard, offering a contained, reflective space. It is a vital stop for anyone interested in the complex history of Delhi's transition of power in the mid-16th century. |

Nila Gumbad (Blue Dome)

The Nila Gumbad (Blue Dome) is a beautiful mausoleum situated just outside the main walled perimeter of Humayun's Tomb. Its isolation and distinctive architectural features hint at its slightly different and complex history, making it a crucial structure for understanding the diverse construction landscape of 16th-century Delhi.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

Name Origin |

The tomb gets its name from its most distinguishing feature: Nila means 'blue' in Hindi. The dome is covered entirely in bright, glazed blue tilework, creating a vivid splash of color against the red sandstone of the surrounding walls. |

History & Occupant |

The exact occupant remains a subject of historical debate. It is widely believed to be the mausoleum of Fahim Khan, a powerful noble who served during the reign of Emperor Akbar. Its construction date is generally placed around the early 1600s, later than the main Humayun's Tomb. |

Location & Context |

The fact that the structure stands just outside the main complex suggests it was constructed on private land, or slightly after the official garden complex was demarcated. Today, it has been beautifully integrated into the overall site and is reached via a modern footbridge. |

Architecture |

The tomb is notable for its pronounced Persian influence, even more striking than the main Humayun's Tomb. This influence is evident not only in the rich use of blue tiles (a characteristic Persian decorative feature) but also in its octagonal base and high-necked dome. It is built on an irregular octagonal plan, which is unusual for the period. |

Importance to the Visit |

The Nila Gumbad is a good example of colorful tile decoration (kashi kari)—a decorative feature that was used sparingly on the main tomb but richly on other contemporary Mughal and pre-Mughal structures like Isa Khan's Tomb. It visually demonstrates the Mughal rulers’ affinity for Persian aesthetics and their mastery of both stone inlay (like on Humayun's Tomb) and ceramic tiling. |

The Experience |

Its distinctive color and elegant form offer a wonderful visual treat. The dome, shining brightly under the Delhi sun, serves as a brilliant marker and is a fantastic photo opportunity. |

Afsarwala Mausoleum and Mosque

The Afsarwala complex (comprising a mausoleum and an adjacent mosque) is a pristine and elegant architectural unit located within the Humayun's Tomb grounds. It is a classic example of the early Mughal practice of pairing a tomb with a functional mosque, designed to ensure that prayers are continually offered for the soul of the deceased.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

History & Occupant |

The complex was constructed around 1566 AD, placing it contemporary with the main Humayun's Tomb construction. The name Afsarwala means 'belonging to an Officer' or 'Noble'. While the specific identity of the high-ranking court official buried here is unknown, the complexity and quality of the construction confirm his substantial importance in the Mughal hierarchy. |

Afsarwala Mausoleum |

The tomb is a dignified square structure resting on a high plinth (platform). It is built of red sandstone and is crowned with a beautiful, single, prominent white marble dome. This white dome provides a beautiful contrast against the surrounding red sandstone, showcasing the developing Mughal aesthetic. |

Afsarwala Mosque |

Adjacent to the mausoleum is a fine, small-scale mosque built entirely of red sandstone. It features three arched entrances and an elegant façade. This tomb-mosque pairing is an essential characteristic of Mughal funerary architecture, where the tomb is sanctified by the presence of a place for communal prayer. |

Architectural Importance |

The Afsarwala complex demonstrates the consistent design language of early Mughal architecture under Akbar. Its clean lines, simple massing, and contrasting white marble on red sandstone perfectly complement the larger aesthetic of the main tomb, while on a reduced, more intimate scale. |

The Experience |

Located slightly away from the main thoroughfare of the Charbagh, the complex often provides a quieter space for visitors to reflect on the craftsmanship of the period without the heavy crowds of the main mausoleum. It offers a clear, undisturbed view of a complete Mughal funerary unit. |

Mirza Muzaffar Hussain Mausoleum

Note: This structure is located outside the main ticketed complex of Humayun’s Tomb, and primarily located within the adjacent Sunder Nursery complex, but is historically related and sometimes visited together.

This elegant mausoleum is significant because it provides a specific identity often associated with the highly distinctive Nila Gumbad (Blue Dome, detailed in 5.3.1.8), cementing the structure's importance to the Mughal royal lineage.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

History & Occupant |

This tomb is widely believed to house the remains of Mirza Muzaffar Hussain, a high-ranking noble and a person of significant status as the great-nephew of Hamida Banu Begum (Humayun's chief wife and the commissioner of the main tomb). His elite standing within the Mughal court justified a magnificent mausoleum located on the periphery of the main complex. |

Alternate Identity |

It is this specific mausoleum that is often referred to as the Nila Gumbad due to its striking exterior. The confusion in naming reflects the shifting property lines and historical record-keeping of the vast site. |

Architecture |

The structure is an outstanding example of Timurid-Persian funerary art. It is instantly recognizable for its breathtaking use of blue-glazed tiling (kashi kari) covering the dome and exterior, from which it earns its popular name. This intense, vibrant coloring stands in stark contrast to the more somber red sandstone and white marble of the main tomb. |

Importance |

The structure is a powerful visual demonstration of the strong Persian aesthetic preferred by the early Mughals, particularly in funerary art. It shows the Mughal court's willingness to use both the highly refined stone-inlay techniques of the main tomb and the traditional, colorful glazed tiles favored by their Timurid ancestors. |

The Experience |

Whether you refer to it by name or its color, the mausoleum is a crucial visual element of the complex, representing the high status afforded to important nobles and demonstrating the various architectural influences at play during Akbar’s reign. |

Chota Batashewala Mausoleum

Note: This structure is located outside the main ticketed complex of Humayun’s Tomb, and primarily located within the adjacent Sunder Nursery complex, but is historically related and sometimes visited together.

The Chota Batashewala complex is situated within the expansive Sunder Nursery area, adjacent to Humayun's Tomb. While geographically separate from the main complex, this site is a crucial architectural link, representing high-status burial practices from the late Mughal period and contributing significantly to the wider funerary landscape of Nizamuddin.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

Location & Context |

This complex is located in the beautifully restored Sunder Nursery, an area historically part of the Mughal garden system surrounding Humayun's Tomb. Its integration within this landscape highlights the continued use of this sacred area for the burial of high-ranking nobles even generations after Humayun's death. |

History & Status |

The complex, including an important tomb, a mosque, and a gateway, belongs to the later Mughal era, though the exact identity of the high-status individual buried here is often debated. It serves as another prime example of a noble family attempting to emulate the imperial funerary style on a smaller, more private scale. |

Architecture |

The tomb is characterized by its balanced proportions and its distinctive architectural materials. It features a prominent domed structure built primarily of red sandstone, enhanced by the sophisticated use of white marble detailing in the trim, arches, and chhatris. This continuation of the red sandstone/white marble aesthetic shows the enduring influence of Humayun's Tomb. |

The Complex |

Like other contemporary high-status burials, the Chota Batashewala complex forms a complete architectural unit: a mausoleum for the tomb, a functional mosque for perpetual prayer, and an elegant gateway to delineate the sacred space. |

Importance to the Visit |

The complex acts as an architectural time capsule, demonstrating how the classic Mughal style evolved and was adopted by the nobility in the centuries following the main tomb's construction. Its beautifully maintained state within the Sunder Nursery makes it an aesthetically pleasing and essential site for appreciating the full scope of Mughal funerary art in Delhi. |

Unknow Mughal's Mausoleum

Note: This structure is located outside the main ticketed complex of Humayun’s Tomb, and primarily located within the adjacent Sunder Nursery complex, but is historically related and sometimes visited together.

Importance: This is one of many unlabeled, smaller tombs scattered throughout the Humayun’s Tomb and Sunder Nursery areas. It underscores the scale of the ‘Dormitory of the Mughals’ and the density of Mughal life and death in this area.

Lakkarwala Burj (Timber Tower)

Note: This structure is located outside the main ticketed complex of Humayun’s Tomb, and primarily located within the adjacent Sunder Nursery complex, but is historically related and sometimes visited together.

The Lakkarwala Burj (Timber Tower) is an intriguing, robust tower situated within the newly restored landscape of the Sunder Nursery. It provides a fascinating glimpse into the less-celebrated aspects of Mughal-era building: the practical and defensive elements often integrated into their expansive garden complexes.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

History & Name |

The name Lakkarwala suggests a connection to timber or a possible storage/watch function, implying that the tower may have originally served as a watchtower or part of a small residential or storage area connected to the overall complex. Its precise original purpose remains a subject of historical debate among archaeologists. |

Architecture |

This is a highly robust structure, designed for utility and stability rather than decorative flair. It is a large, square-based tower built predominantly of stone and rubble masonry, capped with a simple but strong domed roof. Its enduring, heavy construction stands in contrast to the nearby elegant tombs. |

Location & Context |

Located in the Sunder Nursery area, its continued presence today highlights the sheer size and multi-functional nature of the Mughal complexes. These royal enclosures required not just beautiful tombs and gardens, but also administrative, defensive, and logistical support structures. |

Importance to the Visit |

The tower is important because it demonstrates the practical aspects of Mughal life and planning. While the main tomb showcases spiritual and artistic brilliance, the Lakkarwala Burj reminds visitors that the complex was a guarded, well-maintained royal holding, requiring surveillance and security to protect its precious contents and inhabitants. |

Experience |

Admiring the tower allows you to appreciate the full spectrum of Mughal building: from the delicate inlay of the main mausoleum to the sturdy, simple structures necessary for defense and daily administration. |

Sunderwala Mahal

Note: This structure is located outside the main ticketed complex of Humayun’s Tomb, and primarily located within the adjacent Sunder Nursery complex, but is historically related and sometimes visited together.

The Sunderwala Mahal complex, located within the sprawling Sunder Nursery, is an important, high-status burial site from the mid-16th century. Despite its name, Mahal (palace/mansion), the structure is, in fact, an elegant mausoleum and adjacent mosque built for a nobleman, illustrating the complete, formal funerary architecture of the era.

Feature |

Detailed History and Architectural Significance |

|---|---|

History & Function |

Built during the mid-16th century, this complex belongs to the later Lodi or early Sur/Mughal period. It was commissioned for a powerful nobleman and, like other grand burials, the mausoleum was paired with a functional mosque. This ensures the deceased received continuous spiritual benefits from the daily prayers offered within the complex. |

Architecture |

The mausoleum features a sophisticated domed structure built of stone, showcasing the prevalent use of red sandstone and subtle white marble accents. The structure is known for its remnants of decorative tilework, a feature common in the pre-Mughal and early Mughal styles, which adds flashes of color to the exterior. |

The Complex Design |

The entire complex is defined by the impressive scale of its surrounding garden walls, which originally enclosed a formal paradise garden. The design of the Sunderwala Mahal complex perfectly illustrates the blending of tomb and garden architecture common to the era, where the architecture (mausoleum and mosque) was inseparable from the landscaping (the charbagh layout). |

Location & Restoration |

Situated within the Sunder Nursery, the complex has been meticulously restored. Its current pristine state allows visitors to appreciate the original vision of the tomb garden as a harmonious, self-contained unit, removed from the outside world. |

Importance to the Visit |

This structure provides essential context by demonstrating the template that the ultimate Mughal burial—Humayun's Tomb—perfected. It shows how high-ranking nobles used these standardized, symmetrical complex designs to assert their status and ensure their spiritual well-being after death. |

Back to the Day 3 Walking Tour

Where do you want to go now?

Author: Rudy at Backpack and Snorkel

Bio: Owner of Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides. We create in-depth guides to help you plan unforgettable vacations around the world.

Other popular Purple Travel Guides you may be interested in:

Like this Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel Guide? Pin these for later: