Fatehpur Sikri: Self-Guided Walking Tour of the Mughal Ghost City | India Purple Travel Guide

(map, reviews, website)

This is Premium Content! To access it, please download our

Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel GuideJust 23 miles (37 km) west of Agra lies Fatehpur Sikri, a magnificent, fortified city built entirely of red sandstone. Commissioned by Emperor Akbar the Great (r. 1556–1605), this complex served as the capital of the Mughal Empire for a brief but glorious 14 years (from 1571 to 1585). Often referred to as a ‘ghost city’, Fatehpur Sikri is remarkably well-preserved, offering a glimpse into the domestic and administrative life of the 16th-century Mughal court.

Here at Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides, we promote self-guided walking tours.

But we realize that not everybody likes to walk by themselves in a foreign city. So, just in case that you rather go with ab guide: NO PROBLEM! Please see the GuruWalk and Viator tours below.

paid Viator tours

The History and Construction of the City

I. The Spiritual and Political Genesis (1568–1571)

The decision to move the imperial capital from Agra to Fatehpur Sikri was rooted in both profound spirituality and strategic politics.

The Divine Command: Akbar, despite having a massive empire, lacked a male heir. This lack of a surviving male heir was a profound threat to the Mughal dynasty's stability and Akbar's personal legitimacy.

The Pilgrimages: Akbar began making pilgrimages on foot to various holy men and shrines across his empire to seek blessings.

The Sufi Saint: His search led him to Sheikh Salim Chishti, a revered Sufi saint of the Chishti Order, who lived a simple, ascetic life in the village of Sikri.

He made frequent pilgrimages to the village of Sikri to seek the blessings of the revered Sufi saint, Sheikh Salim Chishti. When the saint prophesied to have a son, and Akbar's first son, Prince Salim (the future Emperor Jahangir), was born in 1569, Akbar saw the site as blessed. The relocation was conceived as a monumental act of devotion to the saint.The Foundation: Construction began in earnest around 1571 AD. Akbar chose a ridge of sandstone hills, which was logistically challenging but offered a defensible site. The project was not a simple addition to an existing city; it was the creation of an entirely new imperial capital from the ground up, designed to accommodate an estimated population of over 20,000 courtiers, soldiers, artists, and servants.

The City Wall: Unlike the established Agra Fort, Fatehpur Sikri required a comprehensive urban defense system. Akbar built a monumental 4.4 mile (7km) long city wall (darsana) encircling the settlement. This wall, built of the same local red sandstone, was punctuated by nine massive gateways, including the Delhi Gate and the Agra Gate, defining the formal boundaries of the new capital. There was no pre-existing wall; this was part of the immense, planned construction project.

II. The Builders, Pace, and Scope (1571–1585)

The entire complex was constructed at a furious pace, primarily over a period of 8 to 10 years, a testament to the efficient management of the Mughal workshops (karkhanas).

The Master Builders: While the overall design was overseen by Akbar himself, who was a keen patron and often directed the aesthetic details, the construction relied heavily on local Gujarati, Rajasthani, and Central Indian master masons and craftsmen. This reliance on Hindu and Jain artisans explains the dominant use of traditional column-and-beam architecture and intricate carving styles seen throughout the palaces.

The Building Program: Akbar constructed every necessary administrative, residential, and religious structure simultaneously:

Administrative Heart: The Diwan-i-Aam (Public Audience) and Diwan-i-Khas (Private Audience).

Religious Center: The enormous Jama Masjid and the subsequent towering Buland Darwaza.

Residential Quarters: The elaborate palaces for his three main wives (Jodha Bai, Ruqaiya Begum, and Salima Sultan Begum), the Panch Mahal, and smaller houses like Birbal’s.

Utility Structures: Reservoirs, treasury buildings, mints, stables, and a sophisticated internal water system (canals, tanks, and a large artificial lake).

Did He Demolish Old Neighborhoods? While the area was a small village (Sikri) and a Sufi settlement, there is no evidence of extensive prior urban demolition on the scale seen in Delhi or Agra. Akbar built his grand city on a relatively clear, elevated site, integrating the existing settlement of the revered Sheikh Salim Chishti into the final layout (the Jama Masjid complex).

III. The Fatal Flaw and Abandonment (1585)

Despite the architectural splendor, the political zenith of Fatehpur Sikri was tragically short-lived.

The Water Crisis: The primary reason for the relocation was chronic water scarcity. The large artificial lake built to supply the city proved insufficient. The sheer population growth and the dry climate of the region drained the water reserves, making the city unsustainable.

Strategic Needs: Secondary reasons for the move included strategic military requirements. By 1585, the Mughal empire needed to focus its military attention on the turbulent northwest, making the centralized location of Lahore a more suitable capital for managing the frontier.

The Frozen Legacy: When Akbar left, the city was simply decommissioned, not destroyed. It was left empty and preserved almost perfectly by the climate, allowing historians and visitors today to experience Akbar’s unique vision exactly as it was meant to be seen.

The Signature Architecture: A Cultural Fusion

The architecture of Fatehpur Sikri is its most enduring legacy, representing the peak of Akbar's secular, syncretic philosophy, Sulh-i-Kul (Universal Peace).

Primary Material: The entire city is built from locally quarried red sandstone, giving the complex a cohesive, dramatic color palette.

The Fusion Style: Unlike the Persian-heavy style of his grandfather Babur, Akbar blended diverse traditions:

Mughal/Persian: Seen in the large domes, pointed arches, and the overall symmetrical layout.

Hindu/Jain: Found in the traditional flat ceilings, deep overhanging chajjas (eaves), and the use of carved brackets (a key feature of Rajput architecture).

Gujarati/Rajasthani: Highly visible in the ornamentation and the structure of the zenana (women's quarters), reflecting the styles of his Rajput queens.

Why You Should Visit

Fatehpur Sikri is a UNESCO World Heritage site and an essential stop between Agra and Jaipur because:

It is a Time Capsule: Since it was never rebuilt or repurposed by subsequent rulers, it remains exactly as Akbar left it, providing a unique architectural snapshot of a single, brief moment in Mughal history.

Perfect Preservation: The dry climate has kept the intricate stone carvings in remarkable condition.

The Scale: The size and ambition of the complex are awe-inspiring.

Self-Guided Walking Tour of Fatehpur Sikri

Admission Fee Note: There are two distinct areas in Fatehpur Sikri, each with its own entry requirements:

1. Imperial/Palace Complex: Requires a single, paid admission ticket.

2. Religious Complex (Jama Masjid): Admission is generally free, as it is a working religious site. However, there are separate fees for the Buland Darwaza entrance (if arriving from the outside) and local guides/services.

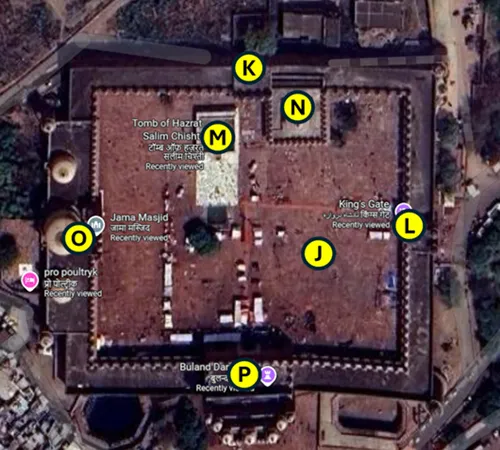

A = Diwan-i-Am

B = Diwan-i-Khas

C = Turkish Sultana's Palace

D = Anup Talao

E = Hauz-i-Shirin

F = Panch Mahal

G = Mariam's House

H = Jodhbai’s Kitchen

I = Jodhbai's Palace

J = Jama Masjid

K = North Gate

L = Badshahi Darwaza

M = Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti

N = Royal Cemetery with Tomb of Islam Khan

O = The Iwan (Sanctuary Portal)

P = Buland Darwaza (The Magnificent Gate)

I. The Imperial & Private Palaces

This section was the heart of the Mughal government and royal residence, built entirely of red sandstone.

A = Diwan-i-Am

B = Diwan-i-Khas

C = Turkish Sultana's Palace

D = Anup Talao

E = Hauz-i-Shirin

F = Panch Mahal

G = Mariam's House

H = Jodhbai’s Kitchen

I = Jodhbai's Palace

Diwan-i-Am: The Emperor's Court

The Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience) in Fatehpur Sikri was the focal point of the city's administrative life, designed to facilitate direct interaction between the mighty Emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) and his subjects. It embodies the expansive, yet disciplined, nature of Mughal governance.

Location and Scale

The Diwan-i-Am is strategically located within the formal court complex, providing a massive, open space for the public to assemble.

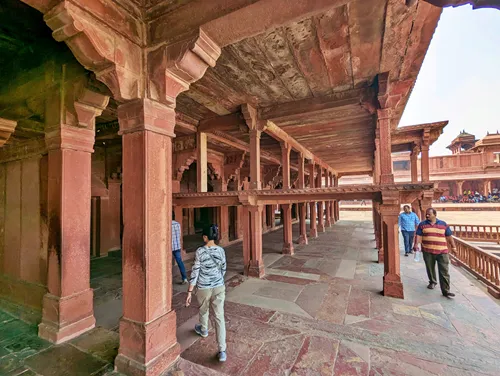

Structure: Unlike the closed, multi-storied palaces, the Diwan-i-Am is characterized by its simplicity: a vast, rectangular courtyard surrounded on three sides by deep colonnades (verandas). These colonnades are divided into bays by red sandstone pillars, offering shade to the courtiers and officials who attended the proceedings.

Material: Like most of Fatehpur Sikri, the structure is built entirely of the beautiful, deeply colored red sandstone.

Function: Justice, Ceremony, and the Jharokha

The Diwan-i-Am was a multipurpose governmental space where the routines of imperial life were carried out daily.

Public Justice: This was the primary venue for the Emperor's public appearances. Subjects, commoners, and lower-ranking officials would gather to present petitions, report regional matters, or appeal for justice directly to the sovereign.

The Jharokha-e-Darshan: The Emperor conducted his morning ritual of showing himself to the public, known as the Jharokha-e-Darshan (Balcony of Appearance), from a large, deep recess built into the back wall of the courtyard. This ritual was crucial for maintaining loyalty, allowing the Emperor to be seen as the ultimate source of power and authority.

Military Parades: The vast courtyard was also used for inspecting troops, receiving ambassadors, and conducting formal military ceremonies.

Contrast with Diwan-i-Khas

The simplicity of the Diwan-i-Am is best understood when contrasted with the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience), which is located nearby.

Diwan-i-Am (Public): Large, simple, and open, built for thousands of people. It was about visual scale and public presence.

Diwan-i-Khas (Private): Small, intimate, and highly complex (featuring the famous central pillar), used only for select high-ranking officials and theological discussions.

This clear separation in design reflects the Mughal hierarchy: maintaining distinct spaces for the general public and for the exclusive inner circles of imperial power.

The Diwan-i-Am, therefore, serves as a powerful architectural reminder of the grand scale of the Mughal Empire and Akbar's personal commitment to a system of visible, accessible, and structured public rule.

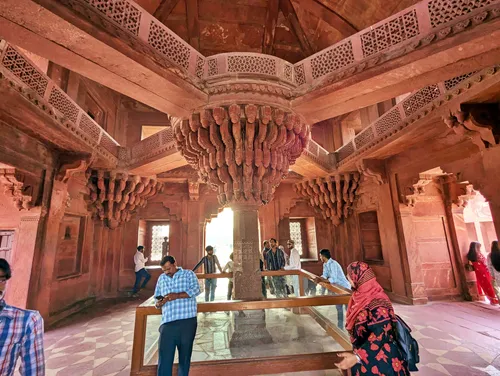

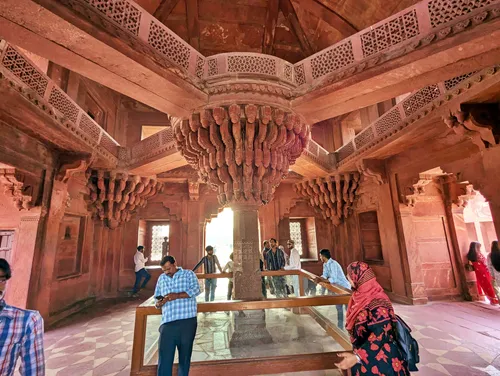

Diwan-i-Khas: The Place of Intellectual Debate

The Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience) at Fatehpur Sikri stands as a monumental statement on the unique governance style and intellectual curiosity of Emperor Akbar. Unlike the sprawling, simple Diwan-i-Am, the Diwan-i-Khas is a small, cube-shaped structure that housed some of the most profound and influential debates in Mughal history.

Architectural Innovation: The Great Central Pillar

What sets the Diwan-i-Khas apart is its revolutionary interior design, which is almost entirely dominated by a single, colossal element:

The Pillar: Rising from the center of the hall is a massive, highly ornate central pillar. This pillar, built of red sandstone, features intricate carvings and is designed in the form of a complex, stylized lotus or kalash.

Akbar’s Throne: At the top of the pillar, a circular platform is supported by twenty-four serpentine brackets that radiate outwards. This platform served as Akbar’s throne. He would ascend via a narrow, concealed staircase built into the wall.

The Bridges: Four narrow, enclosed walkways extend from the central platform to the four corners of the chamber, creating a gallery level that rings the room.

Function: The Four Schools of Thought

The architecture was deliberately designed to reflect the function of the hall: a highly regulated, private space for debate, discussion, and spiritual learning.

The Private Court: The Diwan-i-Khas was used for meeting with a select few high-ranking officials, foreign ambassadors, or religious leaders. It was strictly limited, enforcing the hierarchy of the court.

The Ibadat Khana (House of Worship): It is widely believed that this structure functioned as or adjacent to Akbar’s Ibadat Khana, where he sponsored famous debates between theologians of all faiths: Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Christians, and Zoroastrians.

Symbolic Seating: The layout is brilliantly symbolic: Akbar, elevated on his central platform, was positioned as the unbiased moderator or the axis mundi (center of the world). The four walkways radiating from his throne allowed the four major groups of debaters or officials to be seated on the corner platforms at the same elevated level as the Emperor, symbolically acknowledging their importance while maintaining his central authority.

This ingenious design makes the Diwan-i-Khas not just a beautiful building, but a tangible representation of Akbar's philosophy of Sulh-i-Kul (Universal Peace), where all religious ideas were given a platform for discussion.

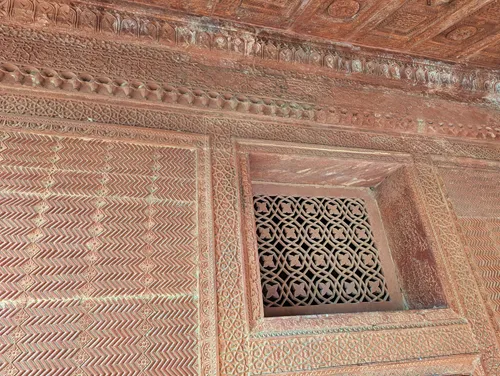

Turkish Sultana's Palace: A Jewel Box of Stone

The Turkish Sultana's Palace (Turki Sultana ka Mahal) at Fatehpur Sikri is regarded by many architectural historians as the most perfectly carved building in the entire city. Despite its relatively small scale, this exquisite structure is a marvelous achievement of craftsmanship and a crucial stop for visitors interested in the intimate details of Mughal court life under Emperor Akbar.

Location and Architectural Scale

The palace is located within the central Zenana (Imperial Harem) courtyard, positioned adjacent to the Diwan-I-Am and close to the famous Anup Talao (the vast ornamental pool).

Structure: The palace is essentially a single, airy chamber surrounded by a low veranda. Its modest size contrasts sharply with the immense nearby halls, emphasizing its function as a highly private, intimate space for a favored royal lady.

Material: Built entirely of beautiful red sandstone, the building stands as an enduring testament to Akbar's preferred construction material.

Architectural Identity: Carving Masterpiece

The lasting fame of the Turkish Sultana's Palace comes almost entirely from its spectacular interior and exterior carvings, which seem to defy the rigidity of stone.

Wooden Aesthetics in Stone: The palace is often described as a translation of a traditional wooden dwelling into stone. The sandstone surfaces are intensely covered with intricate patterns, including geometric designs, delicate arabesques, and naturalistic carvings of birds, animals, and flowing stylized vegetation.

The Veranda: The low veranda surrounding the main room is supported by richly carved columns. The continuous friezes and cornices above display deep, undercut carving, creating a dynamic interplay of shadow and texture.

Dado Panels: Inside the main chamber, the lower wall panels (dado) feature elaborate, highly detailed scenes often interpreted as showing elements of nature and daily life. This level of detail and the mix of motifs showcase the unique syncretic style of Akbar, blending traditional Hindu-Rajput elements with Persian forms.

The Mystery of the Turkish Sultana

The identity of the ‘Turkish Sultana’ is a subject of historical debate, as the name is generally considered an honorary title rather than a literal reference to a Turkish princess.

A Favored Queen: Historians believe the palace was constructed for one of Akbar's most prominent wives. The intense luxury and prime location suggest it belonged to a lady of supreme importance and influence within the Zenana.

Symbolic Naming: The use of ‘Turkish’ may simply refer to a high level of sophistication or a style of ornamentation, as the aesthetic is distinctly Indian Mughal rather than Turkish Ottoman.

The palace stands as a valuable piece of domestic architecture, perfectly illustrating how the Mughal court created spaces that combined artistic detail with the strict requirements of royal privacy.

Anup Talao

The Anup Talao (Incomparable Pool) is the most celebrated ornamental water body in the palace complex of Fatehpur Sikri. It is a structure that perfectly embodies the sophisticated cultural and artistic environment fostered by Emperor Akbar, serving as a stage for music, poetry, and deep scholarly discussions.

Location and Unique Design

The Anup Talao is strategically located in the heart of the private imperial residential area, immediately surrounded by some of the city's most exquisite structures, including the Turkish Sultana's Palace, and the Diwan-i-Khas.

Structure: The Talao is a large, geometrically perfect square tank. Its brilliance lies in its unique central feature: a square stone platform built in the middle of the pool.

The Bridges: Four narrow, decorative stone bridges radiate from the corners of the pool, meeting at the central platform.

Water Management: The pool was designed with a sophisticated water management system that regulated the level and circulation of water, ensuring its purity and effectiveness as a cooling element.

Function: The Mughal Stage

The Anup Talao's architectural design was directly tied to its ceremonial and intellectual function. It was not merely for bathing or cooling but for display and performance:

The Emperor's Seat: The small central platform was used as a miniature stage or throne. The Emperor would occasionally sit here, surrounded by water, to escape the heat and enjoy performances.

Music and Poetry: The pool is famously associated with Miyan Tansen, the legendary musician and one of the ‘Nine Jewels’ (Navaratnas) of Akbar's court. Tansen is said to have performed his mesmerizing compositions while sitting on the central platform, with the water enhancing the acoustics of his music.

Intellectual Mushairas: The Talao also served as a venue for mushairas (poetic symposiums) and private scholarly debates, often involving the diverse religious and philosophical leaders who participated in discussions hosted by Akbar.

Historical and Symbolic Significance

The entire design of the Anup Talao speaks to Akbar's love for cultural synthesis and innovation.

Aesthetic Centerpiece: The pool was the visual centerpiece of the Zenana court, providing a beautiful, calming vista for the royal women who lived in the surrounding palaces.

The Hauz Tradition: It is an evolution of the traditional Islamic hauz (reservoir), transforming a functional element into an elaborate stage and a symbol of royal patronage of the arts.

The Anup Talao remains a favorite spot for visitors, offering a tranquil space and a vivid reminder of the vibrant intellectual and artistic life that flourished during Akbar’s reign.

Hauz-i-Shirin: The Emperor's Colossal Basin

The Hauz-i-Shirin (meaning ‘Sweet Water Tank’ or ‘Sweet Water Pool’) is one of the most remarkable and visually arresting artifacts within the Fatehpur Sikri palace complex. It is not a building, but a single, massive piece of expertly carved stone that speaks volumes about the ceremonial and logistical scale of Emperor Akbar’s court.

Scale and Material Masterpiece

The most immediate impression of the Hauz-i-Shirin is its sheer size. It is a monumental, bowl-shaped vessel carved entirely out of a single piece of deep red sandstone.

Engineering Feat: Weighing several tons, the creation and transportation of this basin to its current location demonstrates the tremendous engineering power and sophisticated logistics available to Akbar's builders in the 16th century.

Aesthetics: The exterior is finished with simple, elegant carving, featuring a thick, braided rope motif around the rim. This restraint in decoration ensures that the focus remains entirely on the object's flawless symmetry and powerful scale.

Theories of Function

Historians debate the precise, daily function of the Hauz-i-Shirin, but all theories point to its ceremonial importance in the imperial court:

Imperial Water Reservoir: The most common theory suggests the basin was used to store purified and cooled drinking water for the Emperor and the royal household. Its capacity would have ensured a continuous, accessible supply, making the basin a vital amenity in the hot climate.

Elephant Trough: Given its colossal dimensions, another theory suggests it may have been used as a massive, ceremonial feeding or watering trough for the Emperor’s favorite elephants or other large, high-status imperial animals.

Hammam (Bath) Basin: It may have served as a large receptacle for mixing scented waters, oils, or rose petals for use in the nearby royal baths, adding a luxurious dimension to the Emperor's hygiene rituals.

Location and Context

Location and Context

The Hauz-i-Shirin stands in a major courtyard on the northern side of the private palace area, near the Panch Mahal. Its prominent placement ensured that it was visible to courtiers and officials as they moved between the public administrative sections and the private royal quarters, serving as a constant reminder of the Emperor's wealth and control over resources.

Panch Mahal: The Five-Story Palace of Winds

The Panch Mahal (Five-Story Palace) is one of the most visually distinctive and architecturally inventive structures in Fatehpur Sikri. Located adjacent to the Zenana (women's quarters), this unique pavilion was constructed by Emperor Akbar and is celebrated for its highly original, multi-tiered design, which fuses Islamic, Persian, and Indian architectural traditions.

Architectural Form and Function

The Panch Mahal is structured as a pyramidal, five-storied palace, built entirely of robust red sandstone. Its design is fundamentally progressive, utilizing open-air construction rather than enclosed walls.

The Structure: Each successive story of the Panch Mahal is smaller than the one below it, culminating in a single domed chhatri (kiosk) at the very top. This tiered, receding plan gives it the appearance of a step pyramid or a magnificent, layered canopy.

A ‘Palace of Winds’: Its open, columned structure was deliberately designed to maximize cross-ventilation and capture cool breezes, functioning as a massive air-cooling pavilion. The royal ladies of the court would use this structure, especially in the evenings, to escape the intense heat of the inner palaces.

The Jalis: While the lowest floor is relatively open, the upper tiers were originally enclosed by delicate, perforated stone screens (jalis) between the columns. These screens provided privacy (purdah) for the royal women while allowing them to discreetly observe the activities in the courtyard below, including the Anup Talao (Incomparable Pool).

Fusion of Styles and Aesthetics

The Panch Mahal is famous for its eclectic use of architectural elements, a hallmark of Akbar's syncretic style:

Pillars and Brackets: The entire structure is supported by an astonishing number of intricately carved columns—84 on the ground floor alone. These pillars showcase a fascinating mix of motifs, including Persian geometric patterns, Hindu-Rajput kalash (pot) and chain designs, and Buddhist-inspired bell and chain motifs.

No Walls: The near-total absence of solid walls emphasizes its function as a recreational and viewing pavilion, not a formal residence. The transition from massive red sandstone at the base to the light, airy canopy at the peak symbolizes the ascent from the earth toward the heavens.

The Panch Mahal is a striking testament to Mughal architects' genius, successfully integrating climate control with complex aesthetic and cultural demands.

Mariam's House / Sunehra Makan: The Golden House of the Empress

The Sunehra Makan (Golden House), popularly known as Mariam's House, is one of the most historically evocative residential structures within the private quarters (Zenana) of Fatehpur Sikri. It is famed for its once-brilliant frescoes and serves as a powerful testament to the cultural fusion and personal lives of the women in Emperor Akbar’s court.

Identity and Location

This palace is situated in the most exclusive area of the residential complex, located just north of the Anup Talao and adjacent to the Panch Mahal.

Official Name (Sunehra Makan): The name Sunehra Makan literally means 'Golden House,' derived from the extensive gold-gilded frescoes and murals that originally covered the interior and exterior walls.

Popular Name (Mariam's House): It is traditionally associated with Mariam-uz-Zamani, the chief Rajput wife of Akbar and mother of his successor, Emperor Jahangir. This association reinforces the palace's high status, indicating it was intended for a queen of great influence.

Architectural Significance and Decoration

The architecture of the Sunehra Makan perfectly encapsulates Akbar's unique style, which synthesized Persian formality with robust Indian regional elements.

Material: Like all of Akbar's structures in Fatehpur Sikri, it is built of richly colored red sandstone.

Rajput Influence: The design is two stories high and follows the traditional trabeated style (post-and-lintel), characteristic of Hindu and Rajput palaces, rather than relying on Islamic arches. The use of elaborate, deeply carved brackets to support the overhanging eaves (chajjas) is particularly prominent.

The Murals: The key feature of the palace—and the reason for its name—is the decoration. Though much of the gold and color has faded due to time and exposure, remnants of the frescoes are still visible on some interior walls. These murals depicted a fascinating array of subjects, including:

Scenes from Hindu epics and mythology.

Persian miniatures, gardens, and floral motifs.

Figures of religious and mythological importance, including a popular motif believed by some to be the Virgin Mary (giving rise to the name Mariam).

Function: A Royal Residence of High Status

As a residential building within the Zenana, the Sunehra Makan was designed for comfort, seclusion, and status.

Intimate Scale: It is smaller and more intimate than the massive public buildings, built to provide a private, comfortable retreat for the Empress.

Climate Control: The two-story design and strategic openings, combined with its proximity to the cool water of the Anup Talao, utilized natural ventilation and cooling techniques, essential for royal living in the hot climate of northern India.

The Sunehra Makan remains a powerful visual document, illustrating not only the grandeur of the court but also Akbar's deep commitment to his policy of religious tolerance and artistic synthesis, reflected vividly in the art created for his own family.

Jodhbai’s Kitchen: The Royal Bawarchi Khana

The structure known as Jodhbai’s Kitchen (Jodhbai ka Rasoi) in Fatehpur Sikri is more than just a place to prepare food; it is an essential piece of infrastructure that reveals the sophisticated logistics required to run Emperor Akbar’s diverse and immense royal household.

Location and Identity

The kitchen complex is strategically situated in the Zenana (women's quarters), located directly adjacent to the great palace traditionally known as Jodhbai’s Palace (or the Harem Palace).

Builder and Material: Like all the major structures in this city, it was built during the reign of Akbar (mid-16th century) using robust red sandstone.

The Name: The name links it to Jodhbai (a popular, though likely historically inaccurate, name for one of Akbar’s Rajput wives). Regardless of who resided in the palace next door, the proximity of the kitchen emphasizes that it was intended to serve the most important and high-status women of the imperial household.

Architectural Clues of Function

The architecture of Jodhbai’s Kitchen is austere and functional, contrasting sharply with the richly carved palaces nearby. Its design is dictated entirely by the practical requirements of cooking for hundreds of people.

Simple Structure: The building consists of a series of simple, rectangular rooms and courtyards. It is less concerned with ornamentation and more with ventilation, heat management, and durability.

Chimneys and Ventilation: The most telling feature is the presence of several open vents and thick walls, designed to channel smoke and heat away from the working areas. Proper ventilation was paramount to ensure the safety and efficiency of the cooks.

Stone Shelves and Hooks: The interior walls feature plain stone shelves and niches where spices, oils, and utensils would have been stored. Stone hooks were likely used to hang cooking implements and meats.

The Logistics of Mughal Cuisine

The existence of a dedicated royal kitchen highlights the incredible complexity of feeding the Mughal court:

Diversity: Mughal court cuisine was a blend of Persian, Central Asian, and various regional Indian styles (especially Rajasthani and Kashmiri), reflecting Akbar's policy of integration. The kitchen would have needed specialized areas and equipment to handle this vast culinary range.

The Kitchen Staff: The actual cooking was conducted by a large, specialized staff of highly skilled male cooks (bawarchis), often supervised by trusted female attendants, who ensured the food was prepared according to the specific dietary requirements (and security needs) of the royal women.

Jodhbai's Palace: The Grand Palace of the Harem

The palace popularly known as Jodhbai's Palace is the largest and arguably the most important residential building in Fatehpur Sikri. Formally known as the Harem Palace or Jahangiri Mahal (as it was later named by his son), this enormous structure was the main hub for the women of Emperor Akbar's court and serves as the crowning example of his early architectural style.

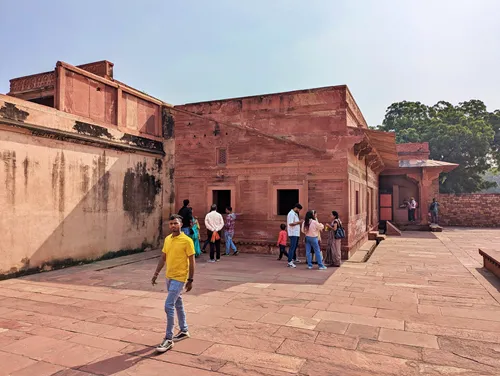

Identity and Scale

The palace dominates the southern portion of the private residential area. Its massive scale and highly fortified appearance distinguish it from the smaller, more refined palaces nearby.

Builder and Time: The palace was constructed by Akbar in the mid-16th century, making it an essential example of the earliest Mughal structures at Fatehpur Sikri.

The Name Misconception: While it is popularly called Jodhbai's Palace, this is a historical misnomer. The legendary Jodh Bai was actually the wife of Jahangir (Akbar's son) and is associated with a different palace in the Agra Fort. However, the name has stuck, and the palace remains universally recognized as the residence of Akbar's chief Rajput wife or queens.

Architectural Fusion: Fortification and Beauty

The design of the Harem Palace perfectly reflects the Mughal policy of cultural synthesis, blending the security of a fortress with the aesthetics of a Rajput manor.

Material and Fortification: It is built almost entirely of rough-hewn red sandstone, giving it a powerful, defensible appearance. The exterior walls are thick and high, and the main entrance—a magnificent gateway guarded by two massive, multi-faceted sandstone columns—suggests the extreme level of seclusion and security maintained for the Zenana (Harem).

Hindu-Rajput Elements: The interior design is dominated by the trabeated style (post-and-lintel construction) rather than arches. Pillars are capped with heavy, elaborately carved brackets and beams that are typically found in Rajput palaces. These carvings often feature naturalistic motifs like peacocks and elephants.

The Courtyard: The palace is organized around a large central courtyard, which provided light, air, and a space for private royal ceremonies, entirely shielded from the outside world.

Climate Control and Residential Function

The layout was specifically designed to cope with the challenges of the harsh North Indian climate:

Seasonal Spaces: The palace includes distinct upper-story apartments and lower chambers. The smaller, enclosed rooms on the ground floor were likely used for the cooler winter months, while the more open, airy apartments on the top floor and the pavilion to the north (near Jodhbai's Kitchen) were utilized during the summer.

Religious Space: A small Hindu temple built into the structure on the western side (now mostly damaged) highlights the palace's dedication to a Rajput queen and underscores Akbar's policy of religious tolerance (Sulh-i-Kul).

II. The Religious Complex (Jama Masjid)

Located on a separate, elevated ridge, this complex is centered on the site where Sheikh Salim Chishti resided and is still an active place of prayer.

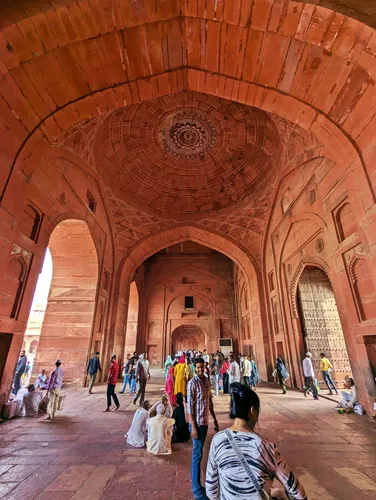

Jama Masjid, Fatehpur Sikri: The Mother of All Mosques

The Jama Masjid (meaning 'Congregational Mosque') of Fatehpur Sikri is not just a building; it is the spiritual heart of the entire imperial city. Built by Emperor Akbar in 1571, it was the first structure completed in the new capital and is considered one of the most magnificent mosques of the Mughal era.

Location and Scale

The mosque is intentionally located just outside the main palace complex, on the western side, accessible to both the royal family and the public.

Size: It is one of the largest mosques in India, featuring a huge inner courtyard (sahn) capable of accommodating thousands of worshippers for the weekly Friday prayers.

Material: It is built primarily of red sandstone, contrasting with the white marble detailing used sparingly on the main entrance and the Buland Darwaza (Triumphal Gate).

Architectural Form and Influence

The Jama Masjid showcases the early Mughal architectural style, heavily influenced by Persian and indigenous Indian design.

The Prayer Hall: The main sanctuary is dominated by three grand, high domes and a colossal, arched portal known as the Iwan. The ceiling and walls were once richly painted, and the prayer niches (mihrabs) are beautifully carved with geometric and floral patterns.

The Courtyard: The vast courtyard, enclosed by high walls and cloisters, provides a sense of quiet grandeur. The southern side of this courtyard is dominated by the monumental Buland Darwaza, and the northern side features a second, smaller, but equally important gate: the Badshahi Gate (Emperor's Gate).

Spiritual Significance: The Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti

The mosque is revered worldwide because its courtyard is the location of a smaller, pristine white marble building: the Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti.

Akbar’s Mentor: Sheikh Salim Chishti was the famous Sufi saint who prophesied the birth of a male heir (who would become Emperor Jahangir) to the childless Emperor Akbar.

The Dargah: Out of reverence, Akbar built his new capital at Fatehpur Sikri and placed his grand mosque around the saint’s residence (dargah). The tomb itself is an architectural masterpiece of white marble with incredibly intricate marble jalis (screens) that are still visited by countless pilgrims seeking blessings.

The Four Monumental Gates

The mosque's architecture is defined by four immense entry points, each serving a distinct function and highlighting the political and religious hierarchy of the Mughal court:

1. Buland Darwaza (The Triumphal Arch)

Location: The colossal Southern Gate of the mosque complex.

Function: This is the public main entrance and a celebration of Mughal power. Built by Akbar to commemorate his victory in Gujarat, it is one of the tallest gateways in the world and serves as a powerful symbol of the Empire's might.

2. Badshahi Darwaza (The Emperor's Gate / East Gate)

Location: The ceremonial gate on the Eastern Wall of the courtyard.

Function: This gate was reserved exclusively for the Emperor and his immediate retinue. It provided a direct, private route for Akbar to enter the mosque courtyard from his nearby personal palace (the Khwabgah), ensuring security and privacy for the royal procession.

3. North Gate (often unnamed)

Location: The major entrance is located on the Eastern Wall of the complex, across from the Iwan.

Function: The gate on the Northern Wall is a smaller, often unnamed, secondary entrance used by courtiers and scholars.

4. The Iwan (The Sanctuary Portal) – not a gate to the outside

Location: The huge, central arched structure on the Western Wall of the courtyard.

Function: This is the most sacred entrance—the monumental façade of the prayer hall itself. As the structure faces West toward Mecca (Qibla), the Iwan marks the direction of prayer and visually dominates the courtyard.

The Jama Masjid complex is the spiritual and cultural high point of Fatehpur Sikri, successfully blending the grandeur of imperial architecture with the intimacy of Sufi devotion.

North Gate: The Courtiers' Passage

The North Gate is one of the three monumental entrances to the Jama Masjid at Fatehpur Sikri. Situated on the northern wall of the vast central courtyard, it plays a critical role in the mosque's overall symmetry and social stratification, providing a secured and prestigious point of entry for the royal court and high officials.

Function and Status

Unlike the towering Buland Darwaza (the public entrance on the south) or the Badshahi Darwaza (the Emperor's private entrance on the east), the North Gate served as the primary entry point for the courtiers, nobility, and visiting scholars.

Elite Access: The gate provided a controlled pathway for the Mughal elite who resided in the imperial quarters to the north of the mosque complex, allowing them to enter and exit the sacred enclosure without mingling with the general public.

Balance and Symmetry: In classic Mughal planning, the North Gate was necessary to balance the architectural weight of the Buland Darwaza to the south, ensuring that the sprawling complex achieved perfect visual symmetry.

A Place for Scholars: Since Fatehpur Sikri was a center for learning and religious discourse, scholars and important religious figures (Ulema) arriving from the imperial areas would have routinely used this gate.

Architectural Characteristics

While it does not possess the sheer vertical scale of the Buland Darwaza, the North Gate is still a substantial and fortified structure, built entirely of red sandstone.

Structure: It is a high, robust archway designed into the mosque's boundary wall. It is typically marked by elegant decorative elements, including white marble or yellow sandstone inlay surrounding the arch.

Features: Like its counterparts, the gate would have included defensive features such as guard chambers within the thickness of the walls and often a set of crowned chhatris (domed pavilions) along the parapet for surveillance and decoration.

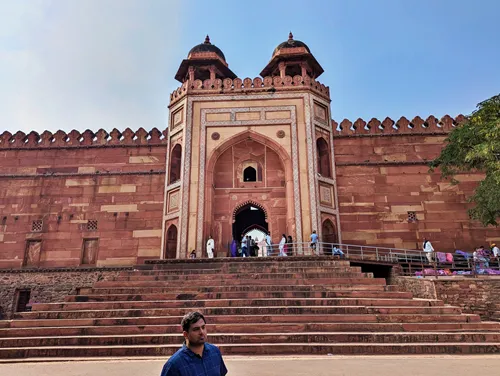

Badshahi Darwaza (The Emperor's Gate)

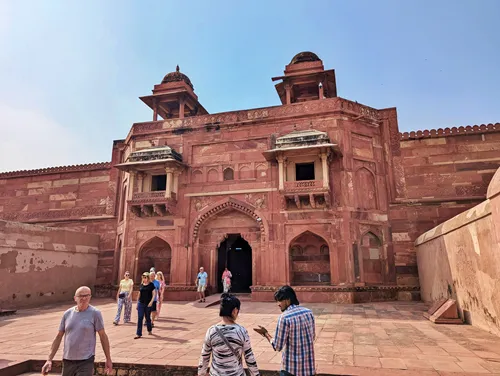

The Badshahi Darwaza (literally, ‘The Emperor's Gate’) is the most architecturally and politically significant entrance to the Jama Masjid at Fatehpur Sikri. It was not merely a way in, but a deliberate statement of the sovereign's sacred duty and private privilege.

Location and Imperial Function

The gate's location highlights its exclusivity and function:

Eastern Wall: The Badshahi Darwaza is situated on the Eastern Wall of the mosque courtyard. This placement is key because the royal private residential complex—including the Khwabgah (Akbar's sleeping chamber) and Jodhbai's Palace—lay directly to the east.

Emperor's Private Access: Its sole function was to provide a secure and immediate passage for Emperor Akbar to move from his private residence directly into the mosque courtyard for the mandatory Friday congregational prayers (Jummah).

Symbol of Sovereignty: This gate represents the highest level of controlled access. It ensured that the sovereign could enter the sacred space without passing through the public crowds at the Buland Darwaza or the courtiers entering via the North Gate, reinforcing the Emperor's unique status.

Architectural Characteristics

The Badshahi Darwaza is a monumental expression of early Mughal military and religious architecture, built from durable red sandstone.

Fortress Design: The gate is designed as a robust, powerful fortress structure. Its thick walls and towers were built to ensure maximum security for the Emperor during his passage.

Decorative Details: The entrance arch is often marked by contrasting white marble or yellow sandstone inlay work, which sets it apart from the uniform red sandstone of the surrounding walls.

The Chhatris: It is typically crowned by multiple elegant chhatris (domed pavilions) along its parapet. These not only provide visual symmetry but also served as essential guard posts overlooking the royal route.

The Badshahi Darwaza remains an iconic symbol of the planning genius of Fatehpur Sikri, seamlessly blending the needs of a fortified court with the demands of imperial devotion.

Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti: The Jewel of the Jama Masjid

Located within the vast courtyard of the Jama Masjid, the Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti (Dargah) is the spiritual nucleus of Fatehpur Sikri. This pristine white marble mausoleum stands in stark contrast to the surrounding red sandstone of the mosque and palace, symbolizing the saint's purity and significance to the Mughal Empire.

The Prophecy that Built a City

The entire city of Fatehpur Sikri owes its existence to the saint who rests here. Emperor Akbar, desperate for a male heir, sought the blessing of Sheikh Salim Chishti, a revered Sufi saint of the Chishti Order. When a son (the future Emperor Jahangir) was born shortly after the prophecy, Akbar, out of devotion, moved his capital to the site of the saint's residence.

A Place of Pilgrimage: The tomb remains a powerful destination for pilgrims today. Many visitors come to tie a thread to the famous marble jalis (screens) around the chamber, praying for the fulfillment of their own wishes, echoing Akbar's original supplication.

Architectural Masterpiece: White Marble Elegance

The tomb is arguably the most exquisite example of intricate carving and design in the entire Fatehpur Sikri complex.

Contrasting Materials: Built between 1580 and 1581, the tomb uses pure white marble imported from Makrana, a stark contrast to the red sandstone used in the rest of the mosque complex.

The Jalis (Screens): The most famous feature is the continuous screen (jali) that encloses the covered passage (verandah). The marble is carved into incredibly delicate, flowing, serpentine patterns that appear almost like lace, providing filtered light and an ethereal glow inside the tomb chamber.

Unique Design: The tomb is also notable for its wide, sloping eaves supported by serpentine brackets—a unique fusion of Persian, Central Asian, and indigenous Gujarati architectural styles.

The Cemetery Area

Just outside the white marble tomb, the large, enclosed courtyard contains numerous graves, making it the Dargah Cemetery (Qabrastaan).

Islam Khan's Tomb: The most prominent red sandstone tomb here belongs to Islam Khan, the grandson of Sheikh Salim Chishti. Islam Khan was an important figure in the court of Emperor Jahangir, serving as a respected Mughal general and the governor of Bengal.

Spiritual Proximity: The tradition of burying important lineage members in the shadow of a saint is an act of spiritual aspiration, ensuring the deceased benefit from the saint's blessed proximity for eternity.

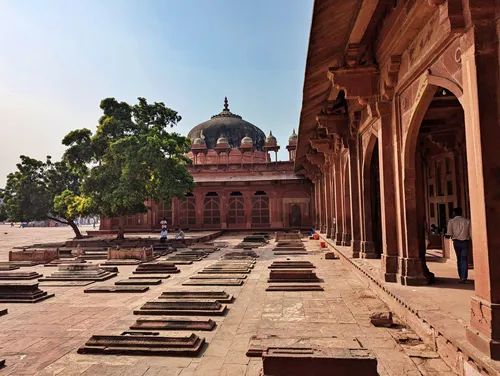

Royal Cemetery with Tomb of Islam Khan

Nestled within the vast, sun-drenched courtyard of the Jama Masjid, the Royal Cemetery is a sacred enclosure that provides a fascinating contrast to the dazzling white marble of the Sheikh Salim Chishti's Dargah. This area, known as the Qabrastaan, is the final resting place for the saint's lineage, underscoring the deep connection between the Mughal throne and the Chishti Sufi order.

The Tomb of Islam Khan

The most prominent structure in this cemetery is the large, dignified mausoleum of Islam Khan.

Identity and Status: Islam Khan was the grandson of Sheikh Salim Chishti. After Akbar's son, Jahangir, ascended the throne, Islam Khan became a major figure in the empire, serving as a trusted general and eventually as the influential Governor (Subahdar) of Bengal. His burial in this prime spot reflects his dual importance: spiritual heir to the Sheikh and a high-ranking Mughal nobleman.

Architecture: The tomb stands as a beautiful example of early Mughal funerary architecture, built entirely of red sandstone. The square tomb is raised on a high plinth and features a central dome surrounded by a cloister of elegant arches and chhatris (domed pavilions) that create deep shadows.

The Uncounted Graves: A Spiritual Dynasty

Surrounding the tomb of Islam Khan are dozens of simpler graves, often laid out in neat rows. These are not unmarked; rather, they signify the wider family and descendants of the great saint.

The Chishti Family: These smaller tombs belong to other members of the Chishti family lineage and important local figures of the era. They typically consist of simple, raised sandstone platforms or platforms topped with plain sandstone tombstones.

Spiritual Proximity: The tradition of placing these graves so close to the saint's Dargah is a profound act of spiritual aspiration. It is an Islamic custom where the deceased are laid to rest in the eternal shadow of the holy person, believing they will benefit from the saint's blessed presence and intercession. The sheer number of these graves speaks to the size and longevity of the spiritual dynasty established by Sheikh Salim Chishti in Fatehpur Sikri.

Spiritual and Physical Contrast

The cemetery area visually reinforces the hierarchy of holiness within the mosque complex:

The Contrast: The tomb of Islam Khan, with its robust red sandstone, stands in immediate and intentional contrast to the ethereal, lattice-like white marble of his grandfather's Dargah. This difference in material highlights the distinction between the sacred (the saint's tomb) and the royal/temporal (the official's tomb).

Proximity to the Saint: The entire area serves the purpose of spiritual proximity. The practice of burying descendants and close associates near the tomb of a saint is an Islamic tradition, as it is believed the deceased will benefit from the holy man's blessings and intercession for eternity.

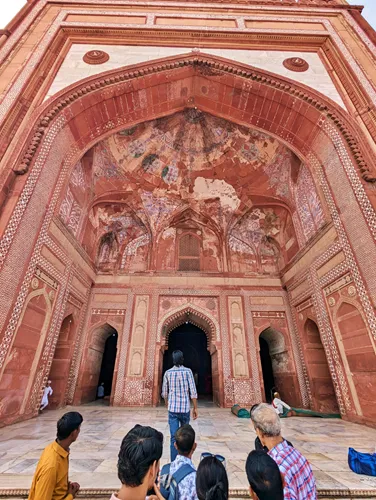

The Iwan (Sanctuary Portal): The Gateway to God

The Iwan is the colossal, central arched structure that dominates the western side of the Jama Masjid courtyard. Unlike the perimeter gates which control entry into the complex, the Iwan is the sacred portal that leads directly into the mosque's Prayer Hall (Sanctuary). It is the architectural heart of Fatehpur Sikri’s spiritual life.

Spiritual Orientation: Facing Mecca

The Iwan's location is dictated by religious necessity, not imperial hierarchy.

Western Wall (Qibla): The Iwan is the centerpiece of the western wall because this direction, known as the Qibla, faces the holy city of Mecca. The entire mosque, and thus the Iwan, is oriented to guide worshippers toward the direction of prayer.

Defining Scale: Its monumental scale is intentional, serving to draw the worshipper's gaze and mind toward the sacred act of prayer. It is the largest single architectural opening in the entire complex, aside from the Buland Darwaza itself.

Architectural Grandeur and Detail

The Iwan is a stunning example of Mughal artistic blending, creating a structure that is both massive and richly detailed.

The Arch: The Iwan is characterized by a huge, rectangular frame (pishtaq) surrounding a deep, recessed arch. This recessed space features tiered vaults known as muqarnas, which add complexity and depth to the portal.

Inlay Work: The red sandstone of the Iwan is lavishly decorated with contrasting white marble and yellow sandstone inlay. This geometric and calligraphic decoration highlights the monumental lines of the portal and contains religious verses and decorative friezes.

Visual Dominance: From any point in the vast courtyard, the Iwan is the single most dominant feature after the domes above it. It commands attention and provides the powerful visual focus necessary for a congregational mosque.

Buland Darwaza (The Magnificent Gate): A Statement of Imperial Power

The Buland Darwaza, meaning ‘High Gate’ or ‘Gate of Magnificence’, is the colossal southern entrance to the Jama Masjid complex. Built by Emperor Akbar, it is one of the most stunning examples of Mughal architecture, serving as a permanent memorial to the empire's might and a triumphant entrance into a sacred space.

Historical and Symbolic Purpose

The gate was not part of the mosque's original design (completed in 1571). Akbar commissioned its construction around 1576-1577 to commemorate his decisive victory over the Kingdom of Gujarat.

Triumphal Arch: It stands as a classic Roman-style Triumphal Arch, built in the Mughal idiom. Its purpose was to symbolize the vastness and success of Akbar’s empire to every visitor, military dignitary, or subject entering the capital.

The Highest Gateway: Built on a natural ridge and elevated further by a high plinth, the Buland Darwaza stands approximately 54 meters (176 feet) high from the ground level outside, making it one of the tallest gateways in the world. Its sheer scale is intended to overwhelm the visitor.

Architectural Grandeur and Details

The Buland Darwaza is a masterpiece of early Mughal design, blending Persian, Central Asian, and Indian architectural styles.

Material: It is constructed primarily of deep red sandstone, contrasting with the careful inlay work done in white marble and black slate.

Design: The main structure is a massive, towering semi-octagonal form dominated by one central monumental arch (Iwan). This arch is framed by smaller side arches and kiosks.

Inscriptions: The central arch contains famous Persian calligraphy, including a crucial inscription that speaks of religious tolerance and the transience of life. This message is attributed to Jesus Christ and reflects Akbar's philosophy of Sulh-i-Kul (universal peace).

Function and Visitor Experience

The Buland Darwaza serves as the public main entrance to the Jama Masjid courtyard.

The Ascent: The approach involves climbing a long, steep flight of steps, which emphasizes the gate's height and provides a dramatic sense of entry into the sacred space.

Contrast: Upon passing through the gate, visitors are immediately met with the serene and vast open courtyard of the Jama Masjid, providing a powerful contrast between the noisy, busy exterior and the quiet, religious interior.

The Buland Darwaza remains the most iconic image of Fatehpur Sikri, perfectly fusing the monumental scale of imperial triumph with the dedication of religious architecture.

Where do you want to go now?

Author: Rudy at Backpack and Snorkel

Bio: Owner of Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides. We create in-depth guides to help you plan unforgettable vacations around the world.

Other popular Purple Travel Guides you may be interested in:

Like this Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel Guide? Pin these for later: