Self-Guided Walking Tour of Agra Fort: The Power and the Prison | India Purple Travel Guide

(map, reviews, website)

This is Premium Content! To access it, please download our

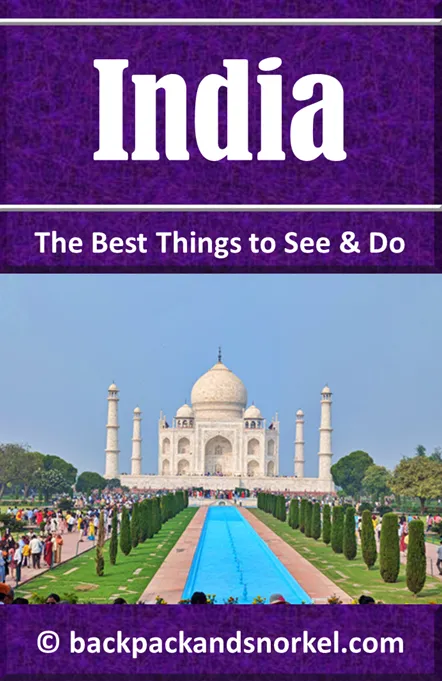

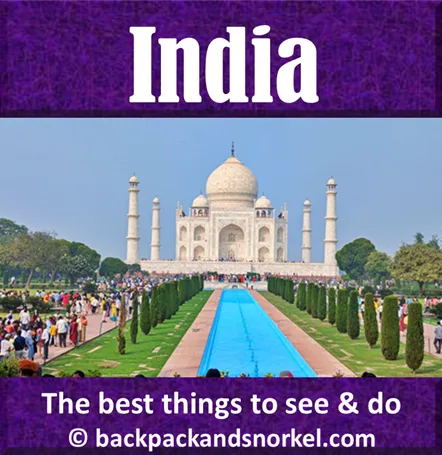

Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel GuideTo truly understand the story of the Taj Mahal, you should also visit Agra Fort. This massive red sandstone fortress is where the Mughal Empire operated, and this is where Shah Jahan, who built the Taj Mahal, spent his final years as a prisoner. It offers a powerful counterpoint to the perfection of the Taj Mahal.

Here at Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides, we promote self-guided walking tours.

But we realize that not everybody likes to walk by themselves in a foreign city. So, just in case that you rather go with ab guide: NO PROBLEM! Please see the GuruWalk and Viator tours below.

free GuruWalk tours

paid Viator tours

Why You Should Visit Agra Fort

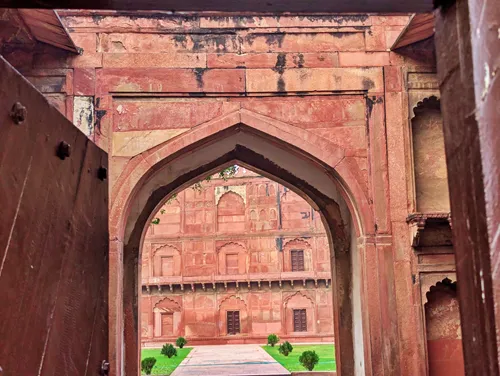

Often overshadowed by the Taj Mahal, the Agra Fort (also known as the Red Fort of Agra or Lal Qila) is a UNESCO World Heritage site and is arguably the most important surviving imperial residence of the Mughal Empire. It is the place from which three great emperors—Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan—ruled the subcontinent.

The Fort offers a unique insight into Mughal life that the Taj Mahal does not:

A Study in Contrast: It shows the stark contrast between the power and military might of the empire (represented by the fort's robust exterior) and the opulence and refinement of the court life inside (represented by its white marble palaces).

Shah Jahan’s Fate: It provides a poignant historical climax: the Fort is where Emperor Shah Jahan was imprisoned by his own son, Aurangzeb. From the small marble balcony of the Musamman Burj, he spent his last eight years gazing at the Taj Mahal, the tomb of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal.

History and Significance

The current structure of the Agra Fort was built primarily by Emperor Akbar the Great (reigned 1556–1605) starting in 1565. It was strategically located on the bend of the Yamuna River.

Emperor |

Contribution |

Significance |

|---|---|---|

Akbar (1565–1573) |

Built the defensive perimeter and the inner red sandstone palaces (like the Jahangiri Mahal). |

Established the Fort as the center of the vast Mughal Empire, shifting the capital from Delhi. |

Shah Jahan (1628–1658) |

Replaced many red sandstone structures with his signature white marble palaces (like the Diwan-i-Khas, Diwan-i-Aam, and Musamman Burj). |

Elevated the architecture from military to luxurious, reflecting the height of Mughal refinement. |

Aurangzeb (1658–1707) |

Imprisoned his father, Shah Jahan, within the Fort. |

Marked the political decline of the era, turning the seat of power into a place of confinement. |

Important: It was not just a military fortress, but really a city within a city, housing the state treasury, the mint, and the court, serving as the nucleus of the largest empire in the region.

Architectural Details: What You Can See

The Fort is crescent-shaped and surrounded by a towering, double-walled 70-foot-high defensive wall made of red sandstone.

Self-Guided Walking Tour of Agra Fort

Only about a quarter of the original fort is accessible to the public today, but the sections that are open are spectacular. Here is what you can see:

1 = Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Memorial

2 = Ticket Booth

3 = Amar Singh Gate

4 = Step Well Akbari Mahal (Ruins)

5 = Jahangir Palace (Jahangiri Mahal)

6 = Hauz-i-Jahangiri

7 = Shah Jahani Mahal

8 = Anguri Bagh (Grape Garden)

9 = Roshnara Ara Pavilion

10 = Musamman Burj / Shahi Burj (The Octagonal Tower): The Heartbreak of the Empire

11 = The Shish Mahal (The Glass Palace): Mughal Opulence and Mystery

12 = Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience): The Throne of Power

13 = Takht-E-Jahangir (Jahangir’s Throne/Slab)

14 = Machchi Bhawan (Fish Enclosure)

15 = Diwan-i-Aam (Hall of Public Audience)

16 = Tomb of John Russell Colvin

17 = Shahi Hamam (Royal Baths)

18 = Shah Jehan's Marble Throne

19 = Ratan Singh Ki Haveli (The Mansion of the Raja)

20 = Moti Masjid (The Pearl Mosque)

21 = The Khaas Mahal: Zenith of Private Mughal Architecture

22 = Meena Masjid: The Emperor's Private Sanctuary

23 = Nagina Masjid: The Gem Mosque of the Royal Ladies

24 = The Bengali Mahal: A Glimpse into Akbar's Zenana

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Memorial

The statue is a modern installation, but it commemorates a pivotal historical episode that took place in Agra in 1666 AD.

Who Was Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj?

To understand the statue, you must understand Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj (1630–1680) was the founder of the Maratha Empire and one of the most celebrated warrior kings in Indian history. Operating primarily from the Deccan Plateau in Western India, Shivaji fiercely challenged the authority of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

Sovereign Ruler: The title Chhatrapati literally means ‘paramount sovereign’ or ‘emperor’, signifying the independent kingdom he carved out.

Swarajya: His mission was the establishment of Hindavi Swarajya (Maratha self-rule), rejecting foreign (Mughal) dominion.

Military Genius: He is revered for his revolutionary military tactics, particularly his mastery of guerrilla warfare (Ganimi Kawa), which allowed his forces to repeatedly defeat much larger Mughal armies.

The Monument: A Symbol of Command

The memorial itself is a large, commanding equestrian statue of Shivaji Maharaj. He is depicted in his royal armor atop a powerful, rearing horse, carrying a sword, and evoking his indomitable spirit and leadership.

The statue's presence in Agra—the seat of the Mughal power he fought—is a powerful statement of historical victory and cultural pride, asserting the lasting legacy of the Maratha Empire.

The Historical Context: The Great Escape of 1666

The statue commemorates the most dramatic event connecting Shivaji directly to the Agra Fort: his detention and subsequent escape in 1666 AD.

The Summons: Emperor Aurangzeb summoned Shivaji to Agra under the promise of high honors and alliance.

The Detention: Shivaji quickly realized he was being humiliated and placed under house arrest inside the Agra Fort (in the vicinity of the Diwan-i-Khas and Musamman Burj).

The Escape: After months of planning, Shivaji orchestrated one of the most legendary jailbreaks in history. He feigned illness and began sending out large baskets of sweets (mithai), supposedly as offerings to Hindu priests and the poor. One evening, he and his son, Sambhaji, hid inside these large baskets, evaded the Mughal guards, and escaped the Fort, traversing hundreds of miles back to the Deccan.

This daring escape, a masterstroke of intelligence and bravery, instantly cemented Shivaji’s reputation as an elusive and brilliant military leader. The Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Memorial in Agra stands as a tribute to a king, and to the singular moment when defiance outsmarted imperial power. It holds deep cultural and historical significance for all of India, marking a pivotal moment in the conflict between the rising Maratha and entrenched Mughal empires.

Ticket Booth

Buy your tickets here.

Amar Singh Gate

The Amar Singh Gate serves as the sole point of entry for modern visitors. This gate immediately confronts you with the sheer scale and resilience of the fortress, setting the stage for the imperial history held within.

The First Impression: Scale and Aesthetic

As you approach the gate, after crossing the drawbridge over the protective moat, you are immediately confronted by its imposing size. The gate is flanked by grand octagonal watchtowers and embedded into the massive red sandstone walls that soar nearly 22 meters (72 feet) high.

The structure dates back to the reign of Akbar the Great (c. 1565–1573), and though the earthy, distinctive red sandstone dominates, you can still appreciate the efforts of later emperors to refine its aesthetic. Look closely at the façade: you can observe the subtle white marble inlays that adorn the sandstone, a decorative touch likely added during Shah Jahan's era to modernize the appearance. While the beautiful, colorful tiles originally used to decorate the exterior are now lost to time, the raw power of the stone remains undeniable.

Military Genius: The Dogleg Defense

The most fascinating aspect of the Amar Singh Gate is not its decoration but its brilliant, deliberate defensive engineering, a hallmark of Indian fort design.

Upon entering, visitors follow a long, ascending ramp flanked by extremely high walls. This is not a straight path; rather, it forces a severe, sharp turn known as a dogleg approach. This architectural choice served a critical military function:

Neutralizing Momentum: The crooked, multi-angled path prevents any invading cavalry or war elephants from building up momentum for a full-force charge. The primary battering ram effect was neutralized.

Target Rich Environment: Attackers were forced to slow down, dismount, and fight on foot, making them vulnerable targets. Guards stationed in the bastions and along the high inner walls had a clear line of sight to fire down onto the bottlenecked intruders.

Narrowing the Focus: The ramp and high walls ensure that the attacking force's size and superiority were rendered useless, forcing the battle into a confined, predetermined killing zone.

A History of Names: Akbar, Lahore, and Rathore

The gate has accumulated multiple names over its nearly five centuries of existence, each name reflecting a different historical or political reality:

Akbar Darwaza Gate: This was the original name given by its builder, Emperor Akbar, simply naming it after himself.

Lahore Gate: The gate was sometimes informally referred to as the Lahore Gate due to its geographical alignment. During the height of the Mughal Empire, Lahore was a vital second capital, a major military center, and the gateway to the vast northwest territories. The gate faced the direction of the crucial imperial road leading to Lahore, hence the nickname.

Amar Singh Gate (Final Name): The gate was formally renamed by Emperor Shah Jahan in the 17th century to honor the Rajput noble, Amar Singh Rathore.

Who was Amar Singh Rathore?

Amar Singh Rathore was a famed Rajput Marwari noble from Jodhpur who served in the Mughal court. He is celebrated for his incredible courage and his dramatic act of defiance in 1644 AD. After a high-ranking Mughal official insulted or humiliated him in the Diwan-i-Aam (Hall of Public Audience), Rathore drew his dagger and slew the official on the spot. Though he was killed while attempting his daring escape, Shah Jahan—despite being the offended party—honored his individual bravery and courage by renaming this important gate after him.

Step Well Akbari Mahal (Ruins)

While the marble palaces of Agra Fort which we will visit soon showcase the dazzling spectacle of the Mughal court, the Step Well Akbari Mahal tells a different, more essential story: that of survival, security, and masterful hydro-engineering. This structure, a massive step well or Baoli, is not a palace but an essential piece of infrastructure that sustained the entire imperial city within the walls.

Location and Historical Context

The Step Well is located within the largely ruined complex of the Akbari Mahal—the original residential palace constructed by Akbar the Great (c. 1565). While Shah Jahan later preferred to build his own marble quarters and demolished many of Akbar’s earlier sandstone structures, the foundation and necessary utilities remained. The Baoli's placement deep within the oldest imperial section confirms its absolute necessity to the fortress's initial design and operation.

Function: Water Security and Strategic Importance

In military and political terms, a successful siege of a fort hinges on cutting off its resources, primarily water. The Step Well ensured the Fort’s autonomy and was vital for Mughal dominance:

Siege Resilience: It provided a massive, guaranteed reservoir of water drawn from deep aquifers, making the fortress self-sufficient and capable of holding out against enemy forces for extended periods, regardless of the Yamuna River's status.

Daily Life: It supplied water not only for the thousands of soldiers and imperial staff but also for the extensive Mughal gardens (like the nearby Anguri Bagh) and the elaborate royal baths (hamams).

Natural Cooling: As a subterranean structure, the Baoli kept its water naturally cool, and the evaporative cooling effect often helped moderate the temperature of the adjacent palace quarters during Agra's brutal summer heat.

The Baoli is therefore a monument to Mughal engineering and the foresight of Akbar, prioritizing function and longevity over mere decorative splendor.

What You Will See Today

Today, the structure is a stark and functional contrast to the delicate marble of the Khas Mahal. You will see a deep well area surrounded by the robust red sandstone that defined Akbar's era.

A Ruined Landscape: The Step Well stands amidst the ruins of the Akbari Mahal, giving visitors a sense of how vast and multilayered the Fort complex once was. It requires travelers to visualize the daily life of an imperial household that was dependent on this one source of water.

Architecture of Utility: While most other visible structures focus on aesthetics, the Step Well highlights pure utility, with strong, simple construction designed to handle immense volumes of water and heavy usage. The presence of steps (the ‘step well’) allowed access to the water even as the levels dropped during the dry season.

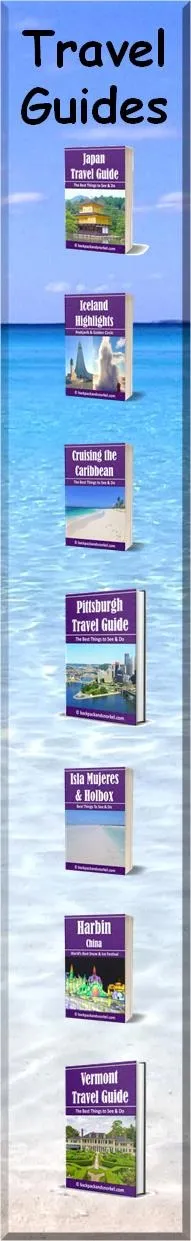

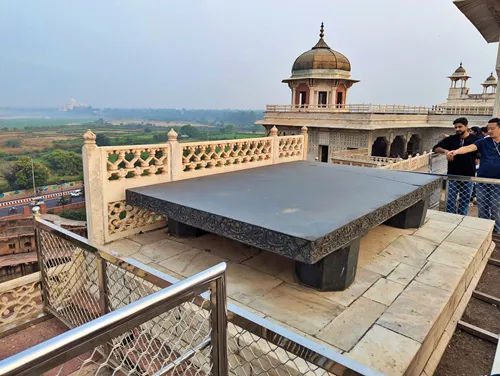

Jahangir Palace (Jahangiri Mahal)

The Jahangiri Mahal, or Jahangir Palace, stands as the most significant and largest surviving residential structure from the era of Akbar the Great (r. 1556–1605). While the Agra Fort is often associated with the marble elegance of Shah Jahan, this palace is a monument to its founder, Akbar, and his philosophy of cultural synthesis and military strength.

This palace is important, because it represents the oldest and most robust layer of Mughal architecture visible in the accessible areas of the Fort, built entirely of enduring red sandstone.

Historical Purpose: The Imperial Zenana

Despite its name, the palace was commissioned by Emperor Akbar around 1569 AD for the use of the royal household, including his son Salim (who would later become Emperor Jahangir).

Residence of Women (Zenana): The primary function of the Jahangiri Mahal was to serve as the chief residence for the imperial women—Akbar's many wives, consorts, mothers, and female relatives. Its colossal size was necessary to house the hundreds of individuals who made up the royal zenana.

A Self-Contained World: The palace is a self-contained world, featuring courtyards, subterranean rooms for cooling, and enclosed terraces, all designed to ensure the privacy and security of the royal ladies, shielded from the public and the male court.

Architectural Masterpiece: Hindu-Persian Fusion

The architecture of the Jahangiri Mahal is a powerful statement of Akbar’s vision of a unified empire, demonstrating a masterful blend of foreign and indigenous styles.

Red Sandstone Dominance: Built entirely of red sandstone, the structure is military in style, contrasting sharply with the delicate marble of the later palaces.

Synthesis of Styles: The design consciously integrates Hindu, Central Asian (Timurid), and Persian elements.

Hindu Influence: Look for the intricately carved stone brackets supporting the rooflines and balconies, which resemble features found in Hindu temples. The square doorways and projected eaves are typical of local Indian architecture.

Timurid Influence: The layout, featuring a large central courtyard and surrounding rooms, draws from the palace traditions of Akbar's Central Asian ancestors.

Absence of Pietra Dura: Notably, the palace lacks the elaborate floral Pietra Dura (inlay work) seen in Shah Jahan's buildings. Instead, the decoration relies entirely on carving, painting, and relief work directly into the stone.

What you will see today

The palace complex is vast and requires time to explore:

The Massive Facade: Visitors encounter a magnificent facade featuring two towering red sandstone watchtowers (burjs).

The Central Courtyard: A large, open courtyard forms the heart of the palace, where light and air could penetrate. The rooms surrounding it were used for sleeping, meetings, and storage.

The Library and Baths: Exploring the various chambers, you can visualize the routines of court life. The Hauz-i-Jahangiri (the enormous monolithic stone tank) is found near the palace, symbolizing the luxury of the imperial baths.

Contrast in Aesthetics: The Jahangiri Mahal stands immediately adjacent to Shah Jahan's white marble structures. This direct contrast is one of the most instructive points in the Fort, allowing travelers to instantly compare the different architectural philosophies of father (Akbar/Jahangir, focused on strength and cultural unity) and grandson (Shah Jahan, focused on refinement and elegance).

Hauz-i-Jahangiri

The Hauz-i-Jahangiri is an unusual and impressive structure within Agra Fort – it is located immediately adjacent to the grand Jahangiri Mahal. Unlike the palaces and courts, this structure is purely utilitarian — a colossal, ornamental bathing vessel that speaks volumes about the Mughals' pursuit of luxury and scale.

History and Importance

The name confirms its association: Hauz means tank or reservoir, and Jahangiri attributes it to Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627). While the Jahangiri Mahal was built by his father Akbar, this specific tank was added later, likely by Jahangir himself, showcasing his love for lavish personal amenities.

Engineering Feat: Its paramount importance lies in its construction. The Hauz is not a vessel built from multiple pieces of stone; it is a monolith—a colossal bowl carved out of a single block of stone. This requires immense labor, sophisticated quarrying techniques, and great effort to transport and install, making it a powerful display of imperial resources and engineering skill.

Symbol of Purity and Luxury: The sheer size of the tank, and the material from which it is carved, symbolizes the emperor's elevated status and the extreme luxury afforded to him. It was a space for ritual purification and sensory pleasure.

Function: The Emperor's Fragrant Retreat

The primary function of the Hauz-i-Jahangiri was to serve as a personal bathing vessel for the Emperor:

The Royal Bath: This was no ordinary tub. The tank was traditionally filled with water mixed with rose water, fragrant essential oils, and herbs before the emperor's ritual baths. The massive volume allowed for a truly immersive and opulent bathing experience.

Aesthetic Display: When not in use for bathing, the Hauz could also function as an enormous, decorative fountain or reservoir, contributing to the cooling and ambiance of the surrounding palace courtyards.

Shah Jahani Mahal

The Shah Jahani Mahal is a pivotal, yet often overlooked, structure in the Agra Fort, as it perfectly captures the moment of architectural transition within the Mughal Empire. Situated between the robust red sandstone palaces of Akbar and the pristine white marble structures of Shah Jahan’s later years, this palace represents the young emperor’s earliest attempts to impose his aesthetic vision on the Fort.

History and Paramount Importance

Built around 1632 AD, the Shah Jahani Mahal predates the pure white marble masterpieces like the Khas Mahal and the Musamman Burj.

The Transitional Style: Its importance lies in the fact that Shah Jahan was constrained by the existing foundations and materials of his grandfather, Akbar. Rather than fully demolishing the older structures (as he did later), Shah Jahan often took existing red sandstone buildings and overlaid them. He achieved a new look by covering the sandstone with thick, polished white shell-lime plaster (stucco) and early marble panels, giving the illusion of a full marble structure.

The Blueprint for Elegance: This palace serves as a blueprint for the mature, refined style that Shah Jahan would perfect at the Taj Mahal. It marks his decisive rejection of the heavy, masculine red sandstone style favored by Akbar and his commitment to the delicate, feminine aesthetic of white marble, which relied on elegance and intricate surface decoration.

Function: A Royal Residence

The Shah Jahani Mahal served as a private residence for the Emperor and his family during the early years of his reign, before the ultimate personal palace, the Khas Mahal, was fully constructed.

Intimate Scale: Compared to the colossal Jahangiri Mahal, the Shah Jahani Mahal is built on a more intimate scale, reflecting Shah Jahan’s preference for smaller, more controlled spaces that emphasized luxury and personal comfort over sheer size.

Early Decoration: It features some of the earliest examples of the signature Shah Jahani decoration, including carved niches, small arched windows, and initial uses of the delicate Pietra Dura (stone inlay work) that would become mandatory in his later palaces.

What the Traveler Sees Today

The palace provides a crucial comparative stop in the Fort tour, showing the development of Mughal taste:

The Visible Layers: The traveler can observe the structural differences between the underlying red sandstone and the white decorative overlay. In areas where the stucco has worn away, the older, red stone foundation is visible, creating a striking contrast and confirming its transitional nature.

The Water Features: Like all Mughal private residences, the palace was designed to maximize comfort. It incorporated elaborate water features, channels, and cascades to cool the air via evaporative cooling during the hot Agra summers.

Connecting the Eras: The palace is positioned strategically, connecting the older Jahangiri Mahal with the later, pure white structures like the Khas Mahal, acting as an architectural bridge between the two great periods of Mughal design.

Anguri Bagh (Grape Garden)

The Anguri Bagh (Grape Garden) is the quintessential Mughal pleasure garden within the Agra Fort. Located directly in front of the exquisite Khas Mahal, Shah Jahan's private residence, it was a lush green space designed not for public display or military use, but for the exclusive enjoyment and privacy of the imperial women (Zenana).

History and Importance

Constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan around the same time as the Khas Mahal (c. 1636), the Anguri Bagh represents the height of Mughal garden design tailored to intimate palace life.

Aesthetics and Cooling: Its importance lay in its seamless integration with the architecture. The garden was designed as an open-air extension of the Khas Mahal, providing cooling shade and scented air to the marble palace. This strategic planting and water circulation were vital for making the imperial quarters habitable during the extreme heat of the Agra summer.

The Charbagh Principle: The Anguri Bagh is one of the best examples of the Charbagh style—the classic Persian and Mughal garden layout defined by four symmetrical quadrants. This geometric perfection symbolized the paradise or ‘heaven on earth’ that the Mughals sought to recreate in their architecture.

Function: The Private World of the Empresses

The Anguri Bagh was the private leisure ground for the royal ladies of the court, primarily the residents of the Khas Mahal and Musamman Burj, including Shah Jahan’s beloved daughters, Jahanara, and Roshanara.

Sensory Experience: Beyond visual symmetry, the garden was intensely functional in a sensory way. It was historically planted with a careful selection of grapevines (hence the name ‘Grape Garden’), fragrant flowers, spices, and fruit trees, ensuring a constant cycle of colors and scents.

Intimacy and Security: Unlike the grander public gardens, the Anguri Bagh was contained within the high walls of the private quarters. Its purpose was to provide a secure, beautiful, and controlled outdoor environment where the royal women could relax, stroll, and socialize away from the view of the external court.

What you will see today

While the grapevines and much of the original, intricate planting have long disappeared, the underlying framework remains perfectly intact:

Symmetry and Structure: Visitors can clearly see the classic four-part division of the garden, separated by pristine, raised walkways and marble-edged water channels. Though the channels may be dry when you visit, they perfectly illustrate how water was channeled throughout the space, emphasizing visual continuity.

The Water Cascade: The garden features small, decorative water cascades and pools that once fed into the main systems, adding the gentle sound of running water, a highly valued element in Mughal garden design.

Architectural Harmony: Standing within the Anguri Bagh, you can appreciate how the pure white marble of the adjacent Khas Mahal and Musamman Burj provides a dramatic backdrop to the greenery, demonstrating Shah Jahan’s commitment to architectural harmony between the built environment and natural landscaping.

Roshnara Ara Pavilion

The Roshnara Ara Pavilion is a charming and architecturally significant component of the Agra Fort, embodying the Mughal obsession with elegance, symmetry, and strategic placement. It is a classic example of a pavilion: an elevated, open-sided structure designed to maximize views and capture cooling river breezes.

Identity and Location

This structure is intrinsically linked to Princess Roshanara Begum (1617–1671), the daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan and Empress Mumtaz Mahal. Roshanara was a highly influential figure who famously supported her younger brother, Aurangzeb, during the war of succession.

Location: The pavilion is strategically situated in the central, high-status area of the Fort, located in the vicinity of the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience) and near the royal residential quarters. Its placement allowed for both prestige and convenient access to the private life of the court.

Aesthetic: The pavilion reflects the refined architectural tastes of Shah Jahan. Its use of highly polished shell-lime stucco over the red sandstone base highlights the transition from the heavy red sandstone to the more delicate, ethereal aesthetic of the mid-17th century Mughal Empire.

Architectural Features and Function

The design of the Roshnara Ara Pavilion was meticulously executed to serve as a luxurious, private retreat for the Mughal royals, most notably the princess herself.

Open and Airy Design: The pavilion is defined by its central open space, bordered by delicately carved arches and columns. This open layout was critical for natural ventilation and allowed for maximum natural light, making it an ideal spot for relaxation and quiet contemplation during the hot Agra days.

Elevated Views: Its raised position grants a panoramic view over the vast surrounding gardens and, crucially, the Yamuna River. The Mughal nobles and royals prized elevated structures that provided unobstructed views, symbolizing their command over the landscape.

Persian and Islamic Elements: The structure features a sophisticated combination of architectural elements. The graceful, repeated arches and the geometric precision of the structure are hallmarks of Islamic design, executed with the delicate craftsmanship of the Mughal style.

Historical Significance and Visitor Experience

While not as large as the Diwan-i-Aam or Khas Mahal, the Roshnara Ara Pavilion has deep historical significance:

A Royal Retreat: Historically, it functioned as a pleasure garden pavilion, a perfect, scenic spot for the royal women to socialize, read, or simply escape the enclosed formality of the palace interiors.

Preservation and Elegance: Today, the pavilion remains a charming and peaceful example of Mughal elegance. Although it may not draw the large crowds of the Fort's main palaces, its historical connection and picturesque setting make it a worthwhile stop. Visitors can stand in the open arches and appreciate the very views that Princess Roshanara would have enjoyed almost four centuries ago, offering a tangible connection to the personal lives of the imperial family.

Musamman Burj / Shahi Burj (The Octagonal Tower): The Heartbreak of the Empire

The Muthamman Burj or Musamman Burj, also known as the Shahi Burj (Royal Tower) or Samman Burj, is the most emotionally resonant structure within the Agra Fort. Built by Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658), it embodies both the height of Mughal architectural grace and the tragic end of its most prolific builder.

Identity and Architectural Clarification

This entire suite of white marble structures is located on the northwestern bastion of the Fort, projecting dramatically over the Yamuna River. Its complex naming often confuses visitors:

Shah Burj (Royal Tower): This is the main, larger, pillared pavilion and the hall that served as the Emperor's private apartment. This is the chamber where the crucial historical events of his confinement took place.

Musamman Burj (Octagonal Tower): This is the smaller, octagonal turret that projects furthest over the wall and is attached to the Shah Burj. Its eight-sided form gives the entire complex its popular name, though it functioned as a private viewing balcony.

Alternative Names: The complex is also known locally as the Muthamman Burj or the Samman Burj.

Architectural Climax and Design

The complex represents the climax of Shah Jahan’s aesthetic style. It utilized pure white marble, moving away from the red sandstone of his predecessors.

Pietra Dura and Jali: The structures are renowned for their delicate marble jalis (latticework screens) and stunning floral Pietra Dura inlays. These intricate carvings, made from semi-precious stones, decorate the walls and columns, symbolizing paradise.

The Fountain Basin: A unique feature within the main Shah Burj hall is the rectangular fountain basin (hauz) depressed into the marble floor. This was an ingenious feature for passive cooling, using the evaporation of water to create a cool, tranquil micro-climate, essential for comfort during the hot Agra summers.

History and Paramount Importance

The historical importance of this complex lies not in its intended function as a pleasure pavilion for the Empress, but in its role as the gilded cage of the deposed emperor.

A Place of Imprisonment: Following his son Aurangzeb’s successful coup in 1658 AD, Shah Jahan was imprisoned here until his death in 1666. Aurangzeb ironically chose this tower because it was the most luxurious place in the Fort, and the one offering a single, clear, continuous view of the Taj Mahal.

A Tragic Final View: For eight years, Shah Jahan was confined to this tower, reportedly passing away in the adjacent hall while gazing across the river at the tomb of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal.

Jahanara's Devotion: The complex is also deeply connected to Jahanara Begum, Shah Jahan’s devoted daughter, who chose to stay with and care for her father in these chambers throughout his long confinement.

The Shah Burj and Musamman Burj complex is therefore the emotional climax of the Agra Fort, encapsulating the dynasty's glory, its ambition, and its most deeply personal sorrows.

The Shish Mahal (The Glass Palace): Mughal Opulence and Mystery

The Shish Mahal, or the Glass Palace, is perhaps the most mysterious and exclusive structure within the Agra Fort. Located beneath the more famous residential quarters of the Khas Mahal and the Muthamman Burj, it is less a palace and more a highly elaborate royal bathhouse or hamam.

Crucially, the Shish Mahal is almost always closed to the general public today due to its extreme fragility and the necessity of its preservation, making its historical description even more vital.

History and Importance

Built by Emperor Shah Jahan around 1637 AD, the Shish Mahal was the ultimate expression of Mughal opulence and hydraulic engineering dedicated to personal use.

Refined Privacy: It was designed as the private, air-conditioned dressing and bathing complex for the women of the imperial zenana, including the empresses and princesses like Jahanara and Roshanara. It ensured absolute privacy and luxury for the royal family’s most intimate rituals.

A World of Illusion: Its importance lies in its unique decorative method: the interior surfaces are inlaid with thousands of tiny, convex mirrors (imported from Syria or Venice) set into intricate plasterwork. This technique created an astonishing, almost psychedelic effect. The palace was designed to be dimly lit by oil lamps or candles, and the flickering light would reflect off the myriad mirrors, making the walls and ceilings shimmer as if they were made of diamonds and stars.

Function: The Royal Hamam and Dressing Chambers

The Shish Mahal served as a complex, multi-functional space optimized for comfort and visual wonder:

Cooling System: As a subterranean structure, it was naturally cooler than the palaces above. Furthermore, it was part of the Shahi Hamam (Royal Baths) complex, featuring sophisticated Mughal engineering where heated water flowed through hidden pipes and marble channels to create steam and warmth in winter, and cool water flowed to provide evaporative cooling in the summer.

The Dressing Rooms: The mirror-inlaid chambers primarily functioned as dressing rooms and an anteroom to the hot and cold baths. The reflective surfaces were not only beautiful but practical, allowing the occupants to admire their elaborate jewelry and silken clothing from every angle in the dim light.

A Hall of Mysteries: The reflective quality of the mirrors meant that two candles could illuminate the entire chamber, giving rise to court legends that the Shish Mahal was a ‘Hall of a Thousand Lights’ or a space of hidden secrets.

What You Need to Know

Since access to the interior is severely restricted, you will experience the Shish Mahal through its exterior and its historical context:

Exterior View: Visitors can view the exterior walls and doorways leading to the Shish Mahal, which are located in the foundations near the Khas Mahal. You will observe the solidity of the white marble/stucco walls that conceal the fragile interior.

Architectural Location: Its placement reinforces the layered nature of the Fort—private, functional structures (like baths and water systems) were frequently placed directly underneath the main residential palaces for convenience and security.

Visualizing Opulence: To fully appreciate the Shish Mahal, you must imagine the interior as the ultimate sensory experience: a cool, fragrant, damp space where the reflection of a single lamp created an illusion of infinite, sparkling depth, a hidden, glittering jewel box at the center of the powerful fortress.

The Shish Mahal represents the pinnacle of Shah Jahan's desire to marry functionality with fairy-tale splendor, creating a world of magic and extravagance for his personal imperial household.

Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience): The Throne of Power

The Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience) represents the political and architectural climax of Emperor Shah Jahan’s tenure in the Agra Fort. Unlike the massive, open-air structure of the Diwan-i-Aam (Public Audience), this smaller, more refined hall was reserved for the highest matters of state, where the future of the empire was decided in hushed tones.

History and Importance

Constructed in pristine white marble by Shah Jahan around 1637 AD, the Diwan-i-Khas marks the decisive shift from military functionality to ultimate imperial splendor.

Exclusivity: This hall was the meeting place for the most powerful nobles, trusted ministers, foreign ambassadors, and visiting princes. Attendance was a sign of immense status, reflecting the Emperor’s personal trust.

Political Theater: This is where highly sensitive topics like military strategy, diplomacy, tax policy, and matters of succession were discussed. The structure itself, built of luminous white marble and delicate Pietra Dura, was designed to convey the immense wealth and sophisticated taste of the Mughal ruler to the world’s most elite visitors.

The Peacock Throne (Historical): The hall’s main chamber was originally intended to house the legendary Peacock Throne (Takht-e-Taus). This throne, studded with millions of rupees worth of jewels, was a dazzling symbol of Mughal wealth and power before it was moved to Delhi and later looted and destroyed.

Architectural Features and Setting

The structure's beauty lies in its intricate detail and flawless symmetry:

Purity of Marble: Built entirely of high-quality white Makrana marble (the same marble used for the Taj Mahal), the hall is a study in Shah Jahan’s mature style.

Pietra Dura Inlays: The pillars, railings, and ceiling borders are adorned with exquisite Pietra Dura—the precise inlay of semi-precious stones (like carnelian, lapis lazuli, and jasper) into the marble to form delicate floral patterns. This detailing contrasts sharply with the plain red sandstone of the nearby older structures.

Acoustic Design: The compact size and high ceiling of the hall were designed to enhance acoustics, ensuring that every word spoken by the Emperor or a petitioner could be clearly heard in the chamber, despite its large open arches.

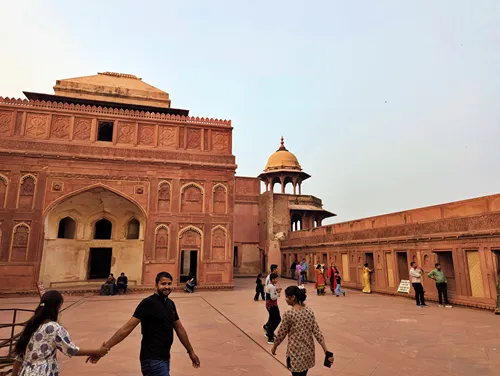

The Thrones and The Black Slab

While the original Peacock Throne is long gone, the courtyard adjacent to the Diwan-i-Khas is historically rich with imperial seating:

Shah Jahan's Marble Throne: Located within the main hall, this beautiful marble seat served as the Emperor’s personal platform for his private court sessions, richly decorated with early floral Pietra Dura.

Takht-E-Jahangir (The Black Throne): Directly outside the hall sits a massive, imposing slab of black slate. This is the older throne of Shah Jahan’s father, Emperor Jahangir. Its dark, heavy appearance and lack of delicate inlay stand in stark contrast to Shah Jahan’s white marble hall, visually symbolizing the shift in Mughal architectural taste from the robust to the refined.

Visitor Experience

The Diwan-i-Khas is a central component of the Fort tour, allowing the visitor to transition from the large, bustling Diwan-i-Aam into a space of hushed elegance.

Sense of Intimacy: The hall feels smaller and more human-scaled than the public audience hall. Stand here and imagine the atmosphere, the intense focus, the weight of the decisions, and the absolute silence that would have fallen when the Emperor spoke.

The Final View: This hall is also tragically linked to Shah Jahan’s imprisonment in the nearby Musamman Burj. This area was the last part of his glorious palace he would have regularly visited before his son Aurangzeb imprisoned him in his private quarters, giving the entire vicinity a profound sense of historical drama.

Takht-E-Jahangir (Jahangir’s Throne/Slab)

The Takht-E-Jahangir, often referred to as Jahangir’s Throne or the Black Throne, is a historically significant and visually arresting object in Agra Fort. It is situated prominently in the courtyard near the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience), and its placement is deliberately intended to create a dialogue with the surrounding white marble architecture.

History and Paramount Importance

The Takht-E-Jahangir is a testament to the power of Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), Shah Jahan’s father.

A Monolithic Creation: The throne is a colossal slab, measuring roughly 10 feet by 10 feet, carved entirely from a single piece of black slate (or touchstone). Like the Hauz-i-Jahangiri, its monolithic nature signifies the immense engineering and logistical power of the Mughal state necessary to transport and position such a massive object.

The Symbol of Lineage: The throne's paramount importance lies in its role as a visible symbol of Mughal dynastic continuity. It represents the power inherited by Shah Jahan. By placing his father's powerful black throne next to his own refined white marble court, Shah Jahan subtly anchored his reign in the robust legacy of his ancestors.

The Persian Inscription: The edges of the slab are historically inscribed with Persian verses that detail the accession of Jahangir to the throne. This inscription is crucial, formally cementing its identity and its historical claim as the official imperial seat during his reign. It was commissioned in 1605, the year Jahangir ascended.

The Titles of the Emperor: The inscription starts by proclaiming the official titles of the newly crowned ruler. Jahangir's names literally translate to mean ‘World-Seizer’ and ‘Light of the Faith’.

Formal Name: Nūr-ud-dīn Muḥammad Jahāngīr (Light of the Faith, Muhammad, World-Seizer).

Imperial Title: Pādshāh-i-Ghāzī (The Victorious Emperor/Warrior of the Faith).The Claim of Divine Right: The inscription establishes the Emperor's right to rule as granted by a higher power, a standard practice in Mughal imperial declarations:

‘From the court of God is the throne's place’.

This sentence establishes that Jahangir's authority is divinely sanctioned, not merely inherited, reinforcing his legitimacy to the powerful nobles who might challenge him.The Lineage and Dynasty: The inscription then formally lists the Emperor's lineage, connecting him directly to the two greatest emperors who preceded him, establishing the chain of Mughal greatness:

‘This noble throne belongs to the lord of the world, son of Akbar Pādshāh, son of Humāyūn Pādshāh…’

This sequence confirms the direct succession:Jahangir (Builder of the slab)

Akbar (The Great Conqueror, his father)

Humāyūn (The second Mughal Emperor, his grandfather)

The Date of Accession: The inscription includes the exact date the slab was commissioned or utilized, corresponding to his accession in 1605, placing a precise historical marker on the object:

‘The completion of this throne was achieved in the month of Muharram in the year 1014 Hijri’. (This corresponds to May/June 1605 AD.)

Function: Public and Private Authority

The throne served multiple functions during the early 17th century, though its final placement by Shah Jahan gave it a symbolic role:

The Seat of Justice: While it was certainly used by Jahangir for various public and private audiences, its most dramatic use was often reserved for ceremonies and for dispensing justice, where the Emperor’s authority was displayed without the added frippery of gemstones or gold.

A Contrast in Style: Its original placement and use predate Shah Jahan’s pure white marble obsession. Its massive, heavy, unadorned appearance represents the architectural preference of the earlier Mughal Emperors—a preference for robust materials and commanding scale over the delicate inlay and refinement that Shah Jahan championed.

Evidence of Damage

Look closely at the slab, and you may see a distinct fissure or crack running across a section of the slab's surface. This is not a natural fault line in the stone but appears to be damage sustained after the slab was installed or moved.

The material itself, dense, heavy black slate, is extremely durable, meaning whatever caused the fissure was a significant, sudden impact.

The Legend of how the crack happened

The story surrounding the crack is what makes the throne legendary. The most commonly accepted version of the tale attributes the damage to an act of disrespect toward the imperial seat:

The Usurper's Hubris: The most popular version states that a courtier, sometimes identified as Asaf Khan (who was either too ambitious or simply acted without permission), sat upon the imperial slab in an act of gross insubordination.

The Imperial Retribution: When this act of disrespect was discovered, the courtier was allegedly thrown from the ramparts of the fort (a deadly fall into the moat or onto the rocks below).

The Stone's Reaction: According to the legend, the heavy stone slab, in an act of sympathetic imperial rage or divine judgment, subsequently cracked in two places, rejecting the touch of the unworthy person and symbolizing the fragmentation of authority caused by the disrespectful act.

The Pragmatic View of how the crack happened

While the folklore is powerful, historians and conservationists generally propose a more pragmatic explanation, though it lacks the drama:

The damage likely occurred during the transport or reinstallation of the enormous, monolithic slab. Moving a single piece of stone this heavy without modern machinery would have been incredibly challenging, and a significant drop or impact during the process could easily cause the large fissure.

The damage could also have occurred during the Maratha sieges or the British occupation of the fort, when the buildings and artifacts were not treated with the original Mughal reverence.

Regardless of the precise cause, the legend of the imperial consequence—where the stone itself rebels against the usurper, is the story that has defined the character of the Takht-E-Jahangir for centuries, turning the physical crack into a powerful, moral lesson about the sanctity of the Mughal throne.

Machchi Bhawan (Fish Enclosure)

The Machchi Bhawan, meaning the Fish Enclosure or Fish House, is one of the largest courtyards within the private quarters of the Agra Fort. It is a massive, two-tiered white marble complex that once served as an elaborate water garden, designed for aesthetics, and as an important setting for imperial life and historical drama.

History and Paramount Importance

The Machchi Bhawan was constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan around the mid-17th century (c. 1637), as part of his overall redesign of the Fort's interior spaces in white marble.

Engineering and Opulence: Its importance lies in its sophisticated hydraulic engineering. The entire courtyard was once filled with marble pools, water channels, fountains, and tanks that were stocked with ornamental fish—hence the name ‘Fish Enclosure’. This served as a beautiful, tranquil setting and provided essential evaporative cooling for the adjacent palaces, like the Diwan-i-Khas.

The Seat of Ceremony: While the Diwan-i-Aam was for public matters, the Machchi Bhawan was often used for private, less formal court ceremonies, evening gatherings, cultural events, and the docking of royal barges when the Yamuna River was high enough.

The Detention of Shivaji: The most historically paramount event associated with the Machchi Bhawan is the temporary imprisonment of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in 1666 AD. The great Maratha warrior king was invited to the court by Aurangzeb, only to be detained and placed under house arrest in or near the Machchi Bhawan. His legendary, daring escape from the fort in a basket of sweets, executed from this area, is a defining moment of resistance against Mughal power.

Architectural Features and Function

The Machchi Bhawan's structure today is largely bare, but its layout speaks to its former grandeur:

Two-Tiered Structure: The complex is built on two levels. The lower level contained the main pools and channels, while the upper level featured pavilions and chambers where the Emperor and courtiers would sit and view the proceedings below.

White Marble: The complex utilizes white marble, consistent with Shah Jahan’s aesthetic, though it lacks the heavy inlay work of the Khas Mahal, focusing more on geometric symmetry and the flow of water.

Water Channels: Look for the extensive network of water channels and slots carved into the marble floor. These were designed to circulate water from the Yamuna River (or the Step Well) to feed the pools and fountains, bringing life and sound to the large space.

The Black Slab Location: The Takht-E-Jahangir (Jahangir’s Black Throne) is also located in the area adjacent to the Machchi Bhawan, confirming its high status as an imperial staging ground.

Visitor Experience

Today, the Machchi Bhawan is an open, sun-drenched marble expanse, allowing the traveler to visualize its past.

Visualizing the Pools: It requires a leap of imagination to see the area filled with sparkling water, colorful fish, and the fragrant mist of the fountains. Imagine the space alive with music and lanterns during a royal festival.

Historical Echoes: Standing on the vast marble surface, you are positioned at the exact site of one of the greatest acts of political defiance in Indian history—Shivaji’s escape.

The Strategic View: From the river-facing side of the Bhawan, you can appreciate the connection to the river, which was the Fort's main artery for transport, trade, and defense.

Diwan-i-Aam (Hall of Public Audience)

The Diwan-i-Aam, or the Hall of Public Audience, is one of the largest and most important structures within the Agra Fort. It was the central operational hub of the Mughal Empire, the place where the emperor met his subjects, commanded his army, and dispensed immediate justice. This hall represents the public face of the emperor, contrasting sharply with the exclusive intimacy of the Diwan-i-Khas.

History and Importance

While the foundations of the structure date back to Akbar's time, the present form was largely constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan around 1631 AD.

The Seat of Power: he Diwan-i-Aam was the stage upon which the daily ritual of imperial governance was enacted. Its paramount importance was its function as the site of the Jharokha-Darshan (the public appearance of the emperor), where the ruler would present himself at dawn to his subjects and the army. This was a crucial ritual to ensure the loyalty of the masses and the psychological control of the vast empire.

The Court of Justice: It was here that the emperor heard petitions from his ordinary subjects and gave summary judgments, cementing his image as the ultimate source of justice and authority.

Military Center: The spacious courtyard in front of the hall was large enough to hold thousands of soldiers, elephants, and cavalry, making it the primary military parade ground and staging area for imperial campaigns.

Architectural Features and Setting

The design of the Diwan-i-Aam is functional, vast, and deliberately built to project scale and authority.

Massive Scale: The hall is a vast, open, three-sided rectangular pavilion supported by dozens of symmetrical, decorative pillars. Its sheer size was necessary to accommodate the massive crowds of soldiers, nobles, and common petitioners who gathered daily.

The Illusion of Marble: Though built primarily of red sandstone, Shah Jahan’s aesthetic influence is visible. The entire structure was originally coated in a meticulously applied, highly polished white shell-lime plaster (stucco). This stucco was so fine that it gave the illusion that the entire hall was constructed of marble, matching his refined tastes without the cost of a full marble rebuild.

The Emperor's Platform (Jharokha): The focal point of the hall is the exquisite, elevated alcove carved into the back wall, known as the Jharokha or Emperor’s Throne Balcony. This balcony, which allowed the emperor to sit above the gathered crowd, was shielded by a marble railing and decorated with floral inlays. This is where the Peacock Throne (Takht-e-Taus) was eventually displayed before its final move to Delhi.

Visitor Experience

The Diwan-i-Aam is often the first major structure visitors encounter after passing through the Amar Singh Gate, immediately setting a tone of imperial grandeur.

Sense of Scale: Standing in the vast open hall, you get a powerful sense of the sheer scale of the Mughal government. Imagine the chaos, the clamor of the soldiers, and the absolute silence that would fall when the Emperor appeared in the Jharokha.

The Throne Alcove: The Jharokha remains the central point of interest. Observe its location at the highest point of the hall, a clear symbolic statement that the emperor was literally above all others.

The Public vs. Private Split: This structure provides the necessary backdrop for understanding the Diwan-i-Khas. The Diwan-i-Aam was for the many; the Diwan-i-Khas (Private Audience) was for the few, a fundamental separation of public administration and high-level strategy that defined the Mughal court system.

Tomb of John Russell Colvin

The Tomb of John Russell Colvin is a stark and unexpected intrusion of British colonial history within the Mughal grandeur of Agra Fort. Unlike the surrounding palaces that celebrate imperial Mughal power, this monument is a sober marker of a dramatic turning point in Indian history: the Great Revolt of 1857.

This tomb’s presence in such a revered Mughal site is significant and represents the moment when the British East India Company assumed military control of the fortress, long after the Mughal emperors had faded into historical obscurity.

History and the 1857 Revolt

The tomb is dedicated to John Russell Colvin (1807–1857), a senior administrator during the British colonial period.

Role in the Empire: Colvin served in various capacities before being appointed the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-Western Provinces (which included Agra) in 1853. This made him the most senior British official governing the region directly from Agra.

The Sepoy Mutiny (1857): When the massive rebellion against British rule erupted in 1857, Colvin and the entire British community in Agra (including soldiers, administrators, and their families) were forced to take refuge inside the heavily fortified walls of the Agra Fort.

Death During Siege: Under the immense strain of the siege, the political turmoil, and the oppressive heat of the summer, Colvin died inside the Fort in September 1857, roughly two months before the British were able to relieve the siege and fully regain control of the area.

Unique Location: He was buried inside the Fort, which had become the central refuge and military headquarters for the British forces. His grave remains here as a permanent, physical reminder of the British struggle and eventual victory in suppressing the revolt in this critical region.

The Structure and Visitor Experience

The tomb is minimalist and European in style, offering a deliberate contrast to the intricate domes and chattris of the Mughal era.

Location: The tomb is located near the Diwan-i-Aam courtyard in an open area that was used by the British as administrative space or for military staging during the siege.

Design: It is a simple, rectangular sarcophagus, a solid, unadorned stone monument typical of European colonial graves. This simplicity stands in stark opposition to the elaborate floral Pietra Dura and marble latticework surrounding it.

The Epitaph: The inscription on the tomb details Colvin’s name, his high office, and the date of his death, firmly anchoring the site to the timeline of the 1857 uprising.

Paramount Importance

The Tomb of John Russell Colvin is paramount for two reasons:

A Timeline Marker: It is the only significant artifact in the Fort that directly speaks to the final chapter of foreign imperial rule, marking the shift from Mughal power to the rule of the British Crown (which took over India's governance shortly after the 1857 Revolt).

A Historical Contrast: Its presence acknowledges the Fort's entire history, not just its Mughal golden age. The Agra Fort served as the ultimate refuge and fortress for four different powers across centuries: the Lodi Sultans, the Mughals, the Marathas, and finally, the British.

Shahi Hamam (Royal Baths)

The Shahi Hamam, or Royal Baths, represents one of the most sophisticated, yet least visible, aspects of the Agra Fort: the imperial system for climate control, hygiene, and ritual purification. This was complex of interlinked chambers and pools, most famously exemplified by the legendary Shish Mahal (The Glass Palace).

History and Engineering Paramountcy

The Hamam complex was primarily constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan (c. 1630s), as a required utility for his new residential marble palaces, particularly the Khas Mahal and Musamman Burj.

1. A Masterpiece of Hydro-Engineering: Its paramount importance lies in its demonstration of advanced Mughal engineering. The Hamam was a self-regulating microclimate. It used a dual system to manage temperature year-round:

1. Winter Heating: Water was heated in huge copper cauldrons and pumped through concealed earthen pipes (nalas) embedded in the thick walls and floors, creating a form of early radiant floor heating and filling the chambers with steam.

2. Summer Cooling: Cool water flowed constantly through marble channels and shallow, decorative pools, utilizing evaporative cooling to maintain a comfortable temperature inside the thick, subterranean walls, often 10–15 degrees cooler than the outside air.

2. Privacy and Hygiene: Located in the subterranean foundations of the private quarters, the Shahi Hamam ensured absolute privacy and met the high standards of hygiene and ritual bathing required by the imperial family.

Function: Purification and Personal Luxury

The Shahi Hamam complex was organized into several rooms, each serving a specific function in the bathing and purification process:

The Dressing Chamber (The Shish Mahal): This was the anteroom, famous for being inlaid with thousands of tiny, reflective mirrors. Here, the royal ladies would disrobe and relax before the main bath. The mirrors were not just decorative; they allowed light from a few lamps to brilliantly illuminate the space for dressing.

The Hot and Cold Baths: Adjacent chambers housed pools for warm, scented baths and cooling dips. These pools were fed by the gravity-driven hydraulic system, often utilizing water drawn from the Yamuna River or the deep Step Well (Baoli).

Sensory Experience: The experience was highly sensual, with fragrant oils, rosewater, and steam creating a damp, scented, and dimly lit atmosphere of relaxation and exclusivity.

Due to the sensitive nature of the interior mirror work and the hydraulic systems, most of the Shahi Hamam complex is closed to the public.

Shah Jehan's Marble Throne

Shah Jahan's Marble Throne, located within the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience), is the purest physical representation of the emperor’s personal aesthetic and his ambition to create an empire defined by beauty. Unlike his father Jahangir's imposing, monolithic Black Throne, this seat of authority prioritizes grace, artistry, and flawless craftsmanship.

History and The Vision of Shah Jahan

This throne was commissioned by Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658) as part of his comprehensive modernization of the Agra Fort, specifically the Diwan-i-Khas area (c. 1637).

Aesthetic Purity: Its paramount importance lies in its material, it is carved from a single block of exquisite, pristine white Makrana marble. Shah Jahan was obsessed with this material, viewing it as the only worthy stone for architecture intended to last eternally (a vision perfectly realized at the Taj Mahal).

A Symbol of Refinement: The throne symbolizes the complete transition of Mughal taste from the heavy, masculine architecture of red sandstone (Akbar's era) to the delicate, feminine architecture of white marble, which emphasized surface decoration, inlay work, and fluid lines.

The Private Audience: This was the seat used by the Emperor when meeting with his most trusted ministers and foreign dignitaries in the exclusive setting of the Diwan-i-Khas. It was a space designed for political intimacy and display of imperial wealth.

Architectural Features: Pietra Dura and Delicacy

The Marble Throne's design focuses entirely on surface decoration, a hallmark of Shah Jahan’s style:

Pietra Dura Inlay: The throne is richly decorated with Pietra Dura, the elaborate technique of inlaying semi-precious stones (such as jasper, carnelian, agate, and lapis lazuli) into the marble to form intricate floral and vine patterns. This delicate work was performed by master craftsmen imported or trained specifically for Shah Jahan's projects, signifying the peak of Mughal artistic achievement.

Elegance and Scale: While still large enough to command authority, the Marble Throne is far more refined and less brutally imposing than the adjacent Black Throne of Jahangir. It is elevated slightly on a platform, reinforcing the emperor's status without relying on sheer mass.

Connection to the Diwan-i-Khas: The colors and patterns of the throne's inlay work were designed to harmonize perfectly with the surrounding marble pillars and arched ceilings of the Diwan-i-Khas, creating a singular, unified vision of imperial opulence.

Ratan Singh Ki Haveli (The Mansion of the Raja)

The Ratan Singh Ki Haveli is one of the less ornate sites in the Agra Fort. It is a large residential compound situated close to the Diwan-i-Aam, and its architecture tells a unique story of political alliance, cultural integration, and the Fort's eventual occupation by non-Mughal forces.

Historical Context and Identity

The identity of the Haveli is layered, reflecting centuries of power shifts:

Mughal Integration: The common attribution to Raja Ratan Singh or a similar high-ranking Rajput noble places its origin in the time of Akbar the Great (16th century). Under Akbar's policy of cooperation (Sulh-i-Kul), Rajput leaders were required to reside within the Fort while serving, necessitating a dedicated family mansion (haveli) built in the local style.

The Jat Footprint (18th Century): The strongest evidence points to a significant renovation or construction by the Bharatpur Jats after they captured and occupied the Fort in 1761 AD. During this period of political decline, the Jats built or remodeled structures to suit their own administrative and residential needs, often adopting the Rajputana style of architecture common to their region.

Architectural Features and Clues

The Haveli visually captures the blend of military necessity and regional style:

Red Sandstone Dominance: The structure is built primarily of red sandstone, confirming its origins within the heavy, protective shell of the early Mughal fortress.

Rajputana Influence: The most defining characteristic is the Rajputana style of architecture, which you can see in the intricate doorways. Look for the:

Curved Brackets: These ornate, decorative supports jut out dramatically, a signature feature found in palaces across Rajasthan, used to support heavy lintels and overhanging eaves (chajjas).

Ornate Arches: The design favors multi-cusped or serpentine arches, blending Persian forms with Hindu carving traditions.

Functionality: As a haveli, the structure prioritized functional living over imperial ceremony, featuring large inner courtyards and numerous chambers designed to accommodate the private, non-courtly lives of the noble families and their retinues.

Importance

The Ratan Singh Ki Haveli is important for two main reasons:

Cultural Synthesis: It demonstrates the physical manifestation of Akbar’s political philosophy, where imperial Mughal power provided the shell (the Fort), but the internal, functional life was sustained by the traditions and architecture of its Rajput allies.

A Timeline of Decline: The 18th-century renovation serves as a vital historical marker. While the fort is famous for its Mughal glory, this haveli stands as tangible evidence that, in the declining centuries of the empire, the fortress became a prize fought over and occupied by new regional powers like the Jats.

Moti Masjid (The Pearl Mosque)

The Moti Masjid, or the Pearl Mosque, is one of the Agra Fort's most exquisite and architecturally significant religious structures. Built entirely of white marble, it stands as a testament to the sublime elegance and spiritual devotion of the Mughal dynasty during its artistic peak.

Moti Masjid is not accessibly for non muslims. Only its white chhatris (meaning canopy or umbrella) and bulbous domes are visible behind the red walls of the fort.

History and Paramount Importance

The Moti Masjid was constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658), likely completed around 1654 AD. It was built almost concurrently with the Taj Mahal and the royal palaces inside the Fort.

A Symbol of Purity: Its paramount importance is its unyielding purity. Unlike the nearby Diwan-i-Aam (which was only stuccoed white), the Moti Masjid is built of solid white Makrana marble. The purity of the white stone symbolizes the purity of the faith and was meant to serve as the Emperor’s private place of worship.

A Royal Mosque: It was the personal Friday Mosque (Jama Masjid) for the Emperor and the high-ranking members of his court and household residing within the Fort complex. This separated them from the public mosque outside the Fort walls, ensuring security and exclusivity.

Architectural Climax: The mosque is considered a climax of Mughal mosque architecture. Shah Jahan refined the style set by earlier Mughal mosques, prioritizing simplicity, symmetry, and perfect proportion over the heavy, decorative elements found in other structures.

Architectural Features and Setting

The Moti Masjid is defined by its quiet grace and geometric perfection:

The Courtyard and Arcades: The mosque centers on a vast, open courtyard (the sahn) paved entirely in white marble. This open area is surrounded by pillared arcades (liwan) where worshippers gathered. The design ensures light and air fill the space.

The Main Prayer Hall: The main structure is topped by three flawless domes constructed of white marble, which swell beautifully against the sky. The dome shape is slightly bulbous, a signature of the Shah Jahani period.

The Scale: While large enough to accommodate the imperial household, the mosque feels contained and intimate compared to the sprawling public Jama Masjid outside the Fort.

The Mihrab and Minbar: Inside the prayer hall, the Mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) and the Minbar (pulpit) are carved with delicate precision, but they maintain the aesthetic of pure marble simplicity, eschewing heavy Pietra Dura found in the palaces.

The Khaas Mahal: Zenith of Private Mughal Architecture

The Khaas Mahal (Private Palace) stands as a testament to the refined taste and architectural ambition of Emperor Shah Jahan within the massive, defensive structure of the Agra Fort. Constructed between 1631 and 1640, this exquisite white marble pavilion marks a pivotal moment in Mughal architecture, symbolizing the transition from the red sandstone style favored by Akbar to the pristine, elegant marble structures that define Shah Jahan's reign.

Location and Royal Function

The Khaas Mahal forms the centerpiece of the imperial residential quarters overlooking the Yamuna River. It is situated behind the massive Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience).

Private Residence: The Khaas Mahal served as the Emperor’s private retreat and sleeping chamber. It was the most intimate space within the palace complex, designed for conducting private affairs, resting, and enjoying the river breezes and garden views.

The Anguri Bagh: The pavilion opens onto the Anguri Bagh (Grape Garden), a formal, four-part Charbagh that provided fragrant shade, sophisticated water channels, and an aesthetic complement to the white marble. The garden enhanced the palace's atmosphere, reinforcing the Mughal tradition of integrating architecture with nature.

Masterpiece of Marble and Inlay

The entire pavilion is constructed of gleaming white marble, which gives it a sublime and airy quality. Its design is characterized by grace and delicacy, a distinct departure from the Fort’s earlier, more robust red sandstone structures.

Architectural Features: The pavilion is composed of a large central hall flanked by two smaller pavilions, all unified by a series of beautiful cusped arches that are visible in the elevation. These arches frame the space perfectly, offering commanding vistas of the surrounding ramparts and the river.

Interior Decoration: While much of the original ornamentation has faded, the Khaas Mahal was once richly decorated. Its interiors featured extensive gold and floral paintings on the ceilings and walls. The marble surfaces are intricately carved with delicate floral patterns and contain detailed examples of pietra dura (stone inlay) work, showcasing the exceptional skill of the Mughal artisans.

Meena Masjid: The Emperor's Private Sanctuary

The Meena Masjid (Gem Mosque) is an intriguing and mysterious structures within the Agra Fort. Unlike the larger, public Pearl Mosque (Moti Masjid), the Meena Masjid was a tiny, utterly private place of worship, built exclusively for the personal use of the Mughal emperor.

Location and Identity

The mosque is located within the most secluded part of the palace complex, near the Shah Burj and the Khaas Mahal. Its placement reinforces its role as a sanctuary reserved only for the emperor and perhaps his immediate family.

Builder and Time: The Meena Masjid was constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan and is contemporary with his surrounding white marble residential buildings (c. 1630s).

Alternative Name: The Meena Masjid is also sometimes referred to as the Masjid-i-Jahan Ara, a name that suggests its strong association with Shah Jahan's daughter, Jahanara Begum. As she was the only family member who remained with the Emperor during his imprisonment, it is likely she used this mosque for her daily prayers as well.

Architectural Seclusion

The architecture of the Meena Masjid speaks entirely to its function as a private sanctuary:

Size and Material: It is a small, unadorned structure. Unlike the great imperial mosques built of red sandstone or ornate white marble, the Meena Masjid is constructed of simple, yet elegant, smooth white marble, reflecting Shah Jahan's preference for the material even in miniature form.

The Missing Decoration: It lacks the decorative calligraphy and intricate pietra dura inlay work that defines the rest of the private quarters. This simplicity was intentional, ensuring the space remained purely focused on contemplation and prayer.

Seclusion: The mosque is designed to be highly secluded and difficult to access. This intentional privacy ensured that the Emperor could perform his prayers (namaz) undisturbed, emphasizing his personal devotion.

Visitor Status

Today, the Meena Masjid is closed to the public. It remains one of the few areas of the private imperial complex that visitors are typically not permitted to enter. Its elusive nature enhances its reputation as a hidden gem and a symbol of the deepest privacy afforded to the emperor within the massive Fort complex.

Nagina Masjid: The Gem Mosque of the Royal Ladies

The Nagina Masjid (Gem Mosque) is a small, exquisite mosque located within the private confines of the Agra Fort. Constructed by Emperor Shah Jahan around 1635, this structure is significant not for its size but for its specific function: it was reserved exclusively as the place of worship for the women of the royal household (Zenana).

Location and Alternative Names

The mosque is positioned adjacent to the Zenana (women's quarters) and stands on the north side of the Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience).

Primary Function: Because of its role, the Nagina Masjid is sometimes referred to as the Zenana Masjid (Ladies’ Mosque). It should not be confused with the Meena Masjid, which was a far more private, tiny mosque reserved solely for the Emperor himself.

Proximity to the Bazaar: Its location allowed the royal women to pray privately and safely, often after visiting the adjacent Meena Bazaar (or Mina Bazaar), the exclusive market where merchants were permitted to sell goods to the sequestered royal ladies.

Architectural Simplicity and Purity

The Nagina Masjid perfectly embodies Shah Jahan’s preference for marble purity and restrained elegance in his private spaces.

Material and Scale: The mosque is a simple yet graceful rectangular structure built entirely of pristine white marble. It is characterized by its small scale, designed to accommodate only the limited number of royal women and their immediate attendants.

Design: The prayer hall is crowned by three beautiful, yet simple, domes and is open to a small courtyard. The columns and walls lack the heavy pietra dura inlay work found in the adjacent palaces. This deliberate simplicity underscores the spiritual purpose of the structure, providing a serene, contemplative atmosphere free from imperial ostentation.

The Jalis: Marble screens (jalis) enclosed the prayer area, ensuring the privacy of the royal women while allowing light and air to circulate—a crucial architectural element for the Zenana structures.

The Bengali Mahal: A Glimpse into Akbar's Zenana

The Bengali Mahal (Bengali Palace) is a major, though often overlooked, palace complex within the Agra Fort. It is historically invaluable because it represents one of the earliest standing palace designs from the reign of Emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605), predating the white marble structures of his grandson, Shah Jahan.

Identity and Location

The Bengali Mahal is located within the large area that constituted the Zenana (Imperial Harem or Women's Quarters). It is situated to the south of the much larger Akbari Mahal and is the most prominent palace of the Hindu-inspired style surviving in the Fort.

Builder and Style: It was built by Akbar in the mid-16th century, making it one of the foundational structures of the Fort’s internal layout.

Alternative Name: Due to its immense size and its position adjacent to the main palace of Akbar, it is often simply lumped in with the larger complex and referred to as part of the Akbari Mahal.

Architectural Significance: Fusion Style

The Bengali Mahal is a vital architectural study piece because it showcases the nascent, groundbreaking Mughal fusion style of Akbar's time, before the refinement of Shah Jahan's white marble era.

Material: It is built entirely of robust red sandstone, the characteristic material of Akbar’s construction.

Hindu Influence: The palace is named 'Bengali' not necessarily because of a Bengali architect, but possibly because its style incorporates distinct architectural elements borrowed from the regions of Bengal and Gujarat, reflecting Akbar's policy of religious and artistic integration.

The Chatris: The roofline features numerous chhatris (domed kiosks), which are traditionally Hindu or Rajput architectural elements.

Lack of Arches: Unlike later Mughal buildings, the Bengali Mahal makes extensive use of trabeated construction—meaning it uses post-and-lintel (or bracket) systems instead of the classic Islamic pointed arches. The walls feature massive, beautifully carved sandstone brackets that support the heavy lintels and eaves.

Function and Interior

As part of the Zenana, the Bengali Mahal was designed to be a private and secluded residence for the royal women, specifically for Akbar's many wives and concubines.

Courtyards and Privacy: The palace is organized around spacious internal courtyards, with small, intimate rooms leading off them. The high walls and minimal external windows ensured the seclusion (purdah) of the royal ladies.

Cooling Systems: Like all imperial structures, it incorporated sophisticated elements for climate control, including thick walls for insulation and channels for water flow to facilitate passive cooling.

Back to the Day 4 Walking Tour

Where do you want to go now?

Author: Rudy at Backpack and Snorkel

Bio: Owner of Backpack and Snorkel Travel Guides. We create in-depth guides to help you plan unforgettable vacations around the world.

Other popular Purple Travel Guides you may be interested in:

Like this Backpack and Snorkel Purple Travel Guide? Pin these for later: